The Eye vs. The Lie

Evidence of photographer Jim Marshall’s wide range of subjects in the late 1960s: transparencies and notes covering Ray Charles, Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane – and a proof sheet depicting Otis Redding and Jimi Hendrix.

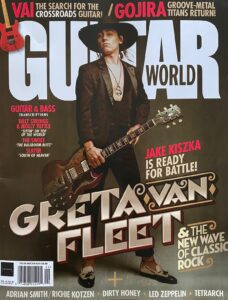

The new issue of Guitar World arrived in the mail yesterday – yep, from time to time an actual print magazine still makes its way to Modern Listener Publishing headquarters. And there was no avoiding the cover image. Guitarist Jake Kiszka of Greta Van Fleet, the new plug-and-play “rock band” for an era when true big rock bands are relics of a distant past. The photo by Alysse Gafkjen is so painfully staged: a posed “rock star” image that screams vanity and shopping-mall-level “edginess” seemingly sprung from a can.

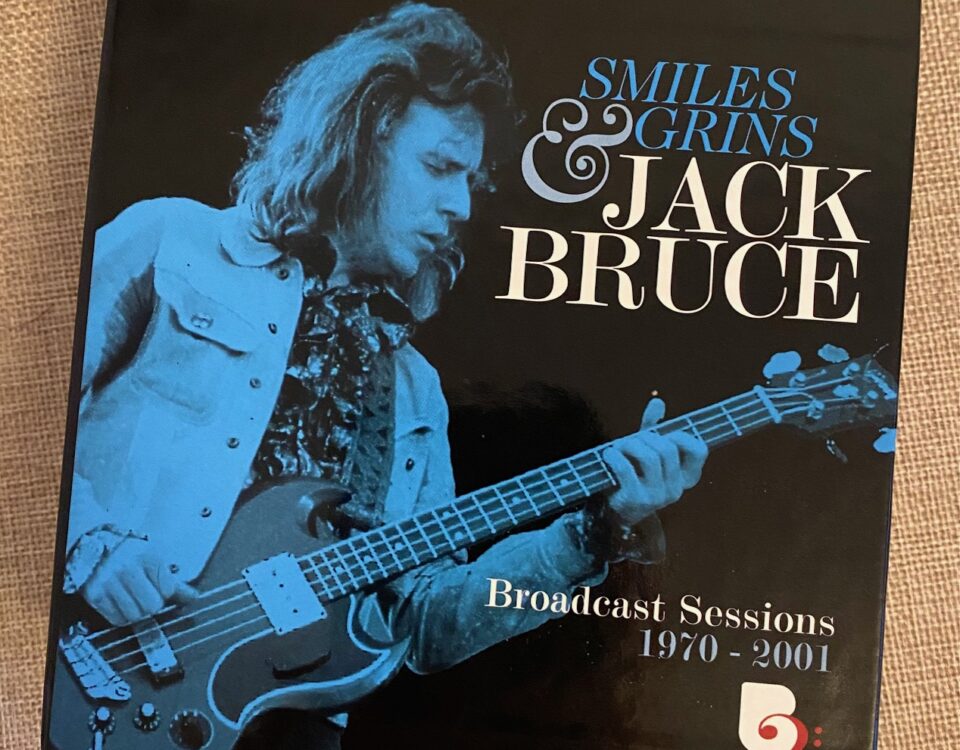

Jake Kiszka strikes his most formidable “rock star” pose while promoting the latest release from Greta Van Fleet.

By contrast, I was recently looking at a book collecting the photographic work of the great Life Magazine photographer Alfred Eisenstaedt. His stunning images are portraits not just of people, but of moments – real moments, with real people living their lives, whether those lives take place in settings of glamour or poverty.

The late Baron Wolman steps from behind the viewfinder, captured in front of a small subset of his iconic photographs.

That sense of photojournalism fully flavored the work of the first great rock photographers on the scene in the lifetime of Jimi Hendrix, including the two late icons Baron Wolman and Jim Marshall. There are too many classic photographs taken by these two men to try to even list examples. Suffice it to say that as rock music became a movement, they were there to open a window on it. Their work allowed you to witness what was happening and how the musicians were candidly reacting to their worlds and the forces of the music industry that were beginning to shape it.

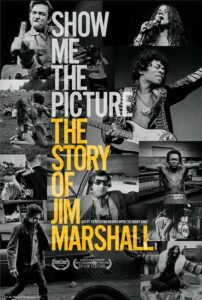

The poster for a recent documentary about the late Jim Marshall reproduces just a tiny selection of Marshall’s stunning images.

Of course, much as Wolman and Marshall were influenced by great photographers before them like Eisenstaedt, Margaret Bourke-White, and Cornell Capa, a second generation of great rock photographers soon built on the tradition of the founders; think of the great work documenting The Clash as seen through the eyes of Pennie Smith.

Pennie Smith at work in the streets, battered road case by her side.

But even as Smith and others were documenting the turbulence of the punk era, the end was growing nigh. Two photographers in particular seemed determined to make their images as much about their own ideas as they were about capturing the intrinsic nature of their subjects: Annie Leibovitz and Norman Seeff.

Seeff removed artists from the chaos of their real lives, instead inserting them into fully controlled environments in which his subjects largely came across as though they were self-consciously channeling fashion model attitudes.

Leibovitz took it all a step further, refocusing her efforts from documenting people within their places to interpreting – and usually promoting – an artist’s image. It seemed as though the process had altered to a new dynamic: “Am I just going to fade into the background and capture you in your reality? No – I’m your creative partner! Let’s get some ideas!” So soon Pete Townshend was far from the heat and light and noise of The Who’s stage, instead applying clinical precision to the task of meticulously smashing a guitar for Leibovitz within the sterile confines of a studio.

Of course, some artists fully embraced the opportunity to control to the greatest extent possible the image presented to the public. Would Madonna have ever scaled the commercial heights she reached without this fundamental revision to the definition of music photography? Without the ability to contrive outrage with her blizzard of carefully controlled “shocking” stances?

But Madonna’s passionate embrace of this photographic shift was just the first mile on the road to where we are now. Find an old issue of Rolling Stone from the late 1960s or Creem Magazine in the 1970s and you just might be shocked by the bracing jolt of reality lurking within the pages. The folks behind those cameras probably didn’t know how good they had it…