Sympathy for the Viewer

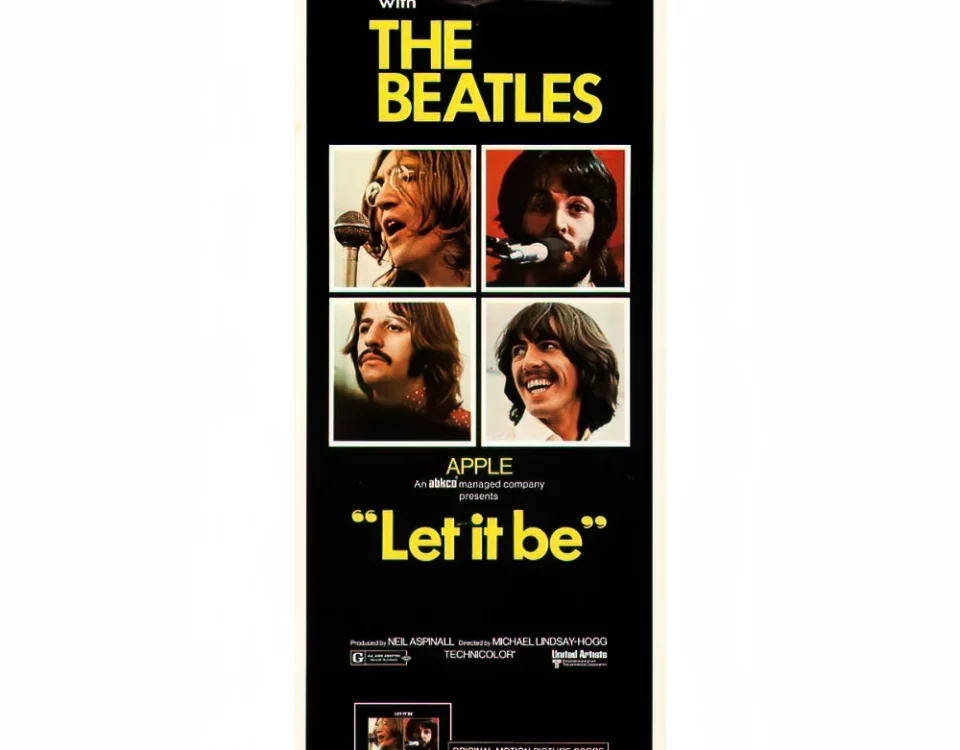

There is a certain, small subset of well-known movies based on or depicting rock music, a subset that has always given me an overwhelming sense that it’s best I steer well clear of these titles.

But as they say, curiosity killed the cat. And I likely would have been better off dead over the weekend when I finally watched the Jean-Luc Godard film Sympathy for the Devil. Or, as it was originally known, One Plus One.

What’s the difference between the two? Apparently, Sympathy for the Devil is simply One Plus One with the final version of the Rolling Stone’s song “Sympathy for the Devil” appended to the ending credit scroll. This action – taken without Godard’s knowledge – sent the director into such a rage that he attacked the film’s producer Iain Quarrier at the film’s premier during the 1968 London Film Festival.

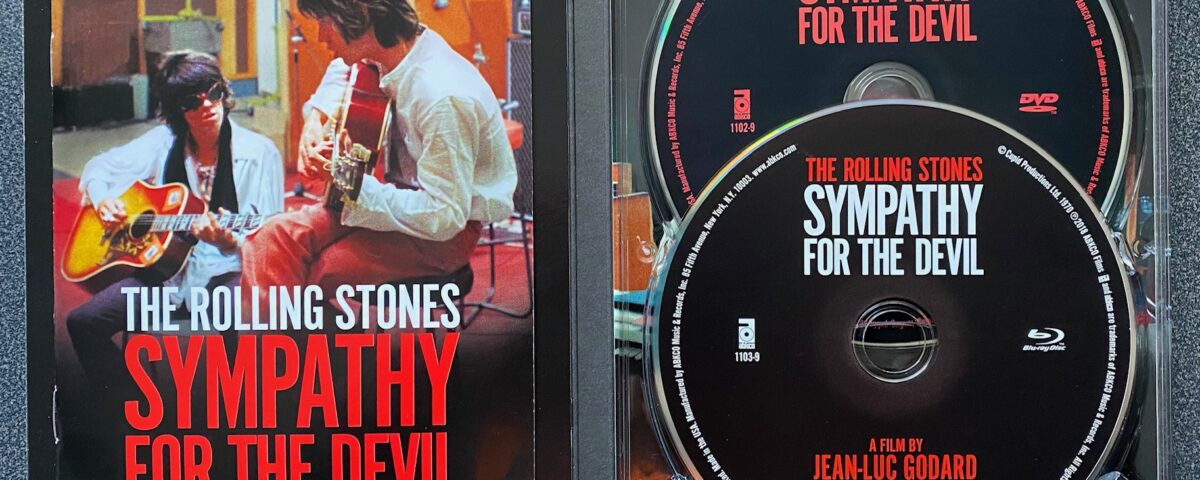

The current commercial packaging of Sympathy for the Devil, offering both DVD and Blu Ray for the complete experience.

Regardless of which version you happen to encounter (and a recent 2018 two-disc release wastefully gives you each entire film on both DVD and Blu Ray), most of the film is astonishing in its feeble attempts to depict and artistically comment on revolutionary aspects of society circa the late 1960s. Whether it is a “radical” female spray-painting slogans around London or a group of Black Panther stand-ins in a junk yard by a river, these interpretative scenes drone on and on and on. The revolutionary rhetoric being spouted by various characters or through rambling voiceovers rapidly attains mind-numbing proportions. I’m surprised Quarrier didn’t attack Godard upon being presented with the final product.

Blind Faith visit the scene of the crime: Olympic Sound Studios, Church Road, Barnes, London. Eric Clapton, Ric Grech, Ginger Baker, and Steve Winwood recorded their lone album at Olympic a year after the Stones recorded “Sympathy for the Devil.” Olympic had relocated its operations to this location in 1966, quickly becoming the hub of rock music creativity in London. Photo: Olympic Cinema

Of course, the saving grace is said Rolling Stones, the band happy to align themselves with a French director with an avant garde reputation. They allowed his cameras full access in Olympic Sound Studios in London early in the summer of 1968. The result is documentation of the creation of the song “Sympathy for the Devil” as it metamorphosizes from a halting acoustic guitar progression to the surging percussion-driven masterpiece that has staked out a piece of rock music history. Some less well-known characters are also thankfully seen at work in the footage, ranging from producer Jimmy Miller and engineer Glyn Johns to keyboardist Nicky Hopkins and percussionist Rocky Dzidzornu. The footage not only captures the magic of recording creativity, but the stretches of intense boredom in the studio as, at times, inspiration is slow in coming. You’ll also witness who is responsible for the “woo-woo” backup vocals heard throughout the song – no spoilers from me.

In the end, enduring the non-Stones portions of this film is very much like listening to Yoko Ono’s contributions on the Live Peace in Toronto 1969 album, where common sense tells you to just turn it off and do something productive with your time. Yet there is the stubborn challenge: Can I survive this? By the time credits roll – with or without “Sympathy for the Devil” heard – it is clear Godard’s film is utterly lacking in any of the charm of its fertile era. Instead, it is a work consumed with taking itself seriously at all costs, a relic of a time when someone with the right hip repute could easily raise enough cash to make a film that (admittedly, says Quarrier) was lacking a key ingredient – a plot.