Cause and Effect: The Sex Pistols and “D.O.A.”

Despite having deep roots in the early UK punk scene as a listener, and in the US punk scene as both a guitarist and a promoter, I surprised myself by never having seen the period film D.O.A.: A Right of Passage. I do think I saw some fuzzy footage from the film back when it was first released around 1981, and Punk magazine’s John Holstrom – who was involved in the production of this film – has pointed out that the initial film release improperly utilized murky work prints. That may have led to my erroneous lack of enthusiasm.

Fast forward almost 40 years to when I spy a copy of the Blu-Ray of D.O.A. Willing to eventually give it another chance, I picked it up – and promptly put it in the I’ll-get-around-to-it-one-of-these-days pile. Well, that day came a week or so ago, and to say this disc was a revelation would be to undervalue it.

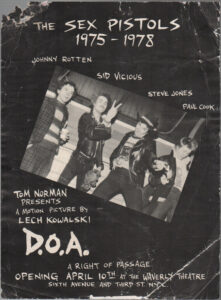

Handbill from the premier of D.O.A.: A Right of Passage, on April 10, 1981 at New York City’s Waverly Theatre.

The main selling point of the film is the priceless footage of the Sex Pistol’s crazed 1978 U.S. tour, one undertaken in a series of odd locales in locations seemingly chosen for the likelihood of audience confrontation taking place. The clarity of the film is far superior to that seen in the initial release, and it all stands as a priceless documentation of one of the strangest series of shows ever.

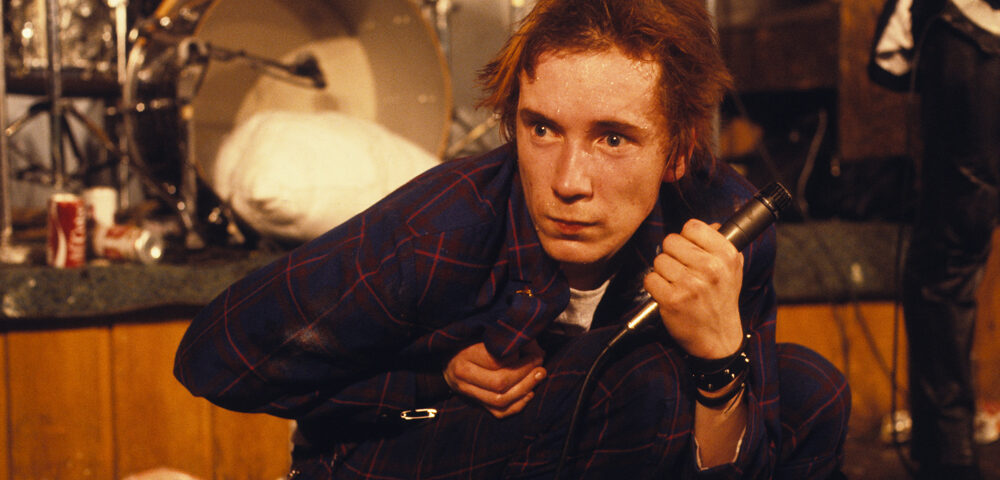

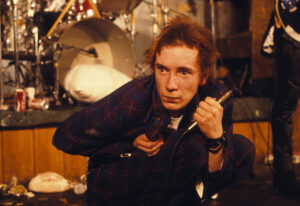

Aside from the antics of “bassist” Sid Vicious, the focus of the Sex Pistols footage is singer Johnny Rotten. While Rotten is seen largely floundering on the large stage at San Francisco’s Winterland during the final gig by the band, at other venues Rotten is laser-focused. Coldly staring down a braying Texas crowd like he’s the one looking at freaks, not vice versa, Rotten is an absolutely riveting presence, one of the greatest commanders of a stage in the history of rock music. These are truly powerful moments captured amidst a chaos of flying debris and barely suppressed violence.

Johnny Rotten (John Lydon) stares down the crowd at the Sex Pistols San Antonio gig on January 8, 1978. (Photo by Richard E. Aaron)

In addition to the coverage of the Pistols’ USA adventures, a hefty segment of the movie ventures through the UK of the late 1970s which spawned the Sex Pistols. In these segments London is portrayed as a dingy and forbidding landscape of cheerless, high-rise public housing – the perfect ground-zero germinator for punk rock.

And there is ample footage documenting the resulting explosions, ranging from haywire glimpses of Jimmy Pursey fronting Sham 69, a self-assured, preening Generation X in their rehearsal space running through “Kiss Me Deadly,” and young Poly Styrene leading X-Ray Spex through a kinetic “Oh Bondage Up Yours!” in front of a wildly unhinged crowd.

Context for the scene at large is given through the eyes of Terry Sylvester, the “singer” of Terry and the Idiots, a band that four decades on is a footnote in punk history. The counterpoint? Bernard Brook Partridge, a stuffy council member who considers the punk movement to be hardly worth the waste of breath required to talk about it. Further enlightenment comes from interviews with folks ranging from Sex Pistols visionary Malcolm McLaren to Midge Ure, drafted from his Scottish power pop band directly into the ranks of founding Sex Pistol bassist and songwriter Glen Matclock’s spinoff Rich Kids. And you’ll not soon forget the interview with Sid Vicious and Nancy Spungen, filmed in their London flat after the Pistols’ demise. This sad footage stands as what may well be the very definition of the word “pathetic.”

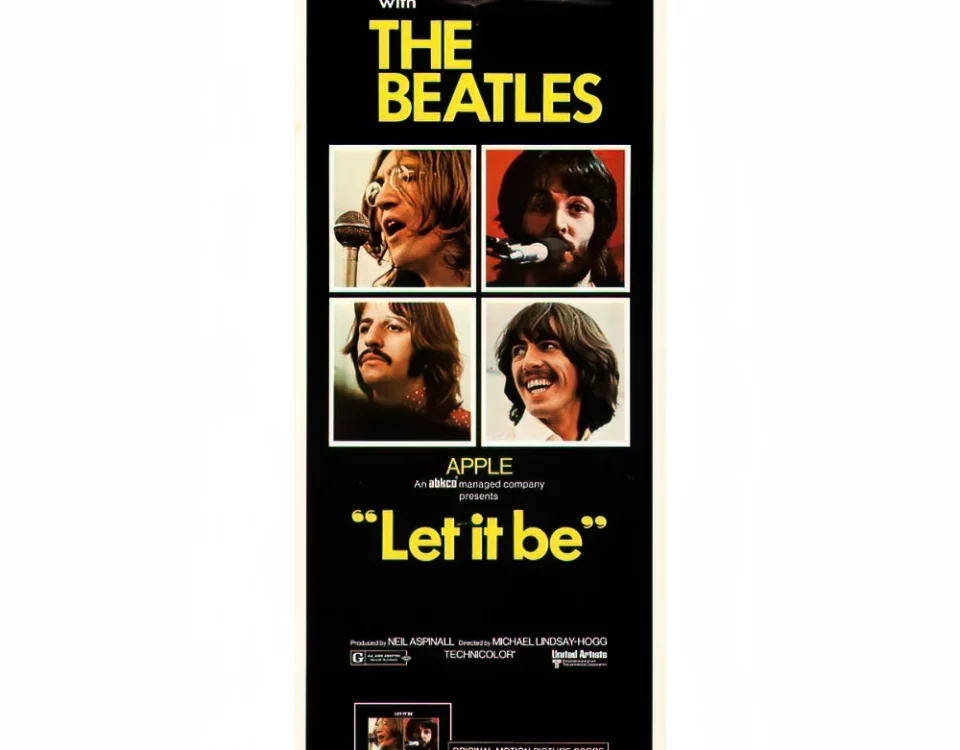

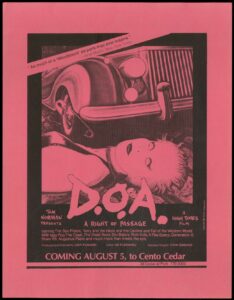

A theatrical poster for a screening of D.O.A. in San Francisco, the city where the Sex Pistols imploded after a short, chaotic US tour.

The film largely came about through the efforts of director Lech Kowalski and a bankroll of extremely shady origins provided by Tom Forcade, founder of High Times magazine. Forcade was “a character” in every sense of the word. But after watching the film D.O.A., I can’t recommend strongly enough that you watch the engrossing feature-length documentary about the making of the film, in which the troops on the ground reveal all. One example: with the Pistols’ U.S. label Warner Brothers refusing to let Kowalski film the Sex Pistols U.S. gigs, the camera crew would show up at the venues, announce they were from a local television station and needed to film for that night’s news broadcast, and barge their way into the chaos, filming a song or two before being kicked back outside.

From end to end, this era was totally unique on many fronts. As a perceptive Billy Idol points out, the punk bands didn’t court the record companies – those companies came charging at them in a commercial feeding frenzy.

I’ve often expressed my belief that the punk movement of the late 1970s was the last time the recording industry was ambushed by something they didn’t see coming or understand. And typically, their reaction at the time was to throw money in an attempt to install financial fencing around it – a tried and true methodology that to some extent worked.

But as John Holstrom points out as he assesses the entirety of the landscape inhabited by D.O.A., immediately in the wake of punk rock came the personal computer and the rise of digital communication. With the instant flow of information, any movement attempting to gestate under the radar would face a nearly insurmountable task.

Fortunately, D.O.A. – and its supplemental material – stands to remind us of a time when, as Joe Strummer once noted, the future truly was unwritten.

The MVD Rewind Collection release of D.O.A.: A Right of Passage contains both a Blu-Ray and DVD as well as a double-sided poster and booklet.

Note: As is sometimes seen in modern-day packaging of films, for some wasteful reason the D.O.A. Blu-Ray is packaged together with the D.O.A. DVD. The only advantage I can think for this is retailers only have to track one item in inventory as opposed to two separate releases, but it is absurd. Regardless, the two-disc “MVD Rewind Collection” release of 2017 is the only Blu-Ray release of this film – and its supplemental material – that I am aware of…