CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: ELECTRIC LADYLAND, SLIGHT RETURN

© Frank Moriarty, 2019

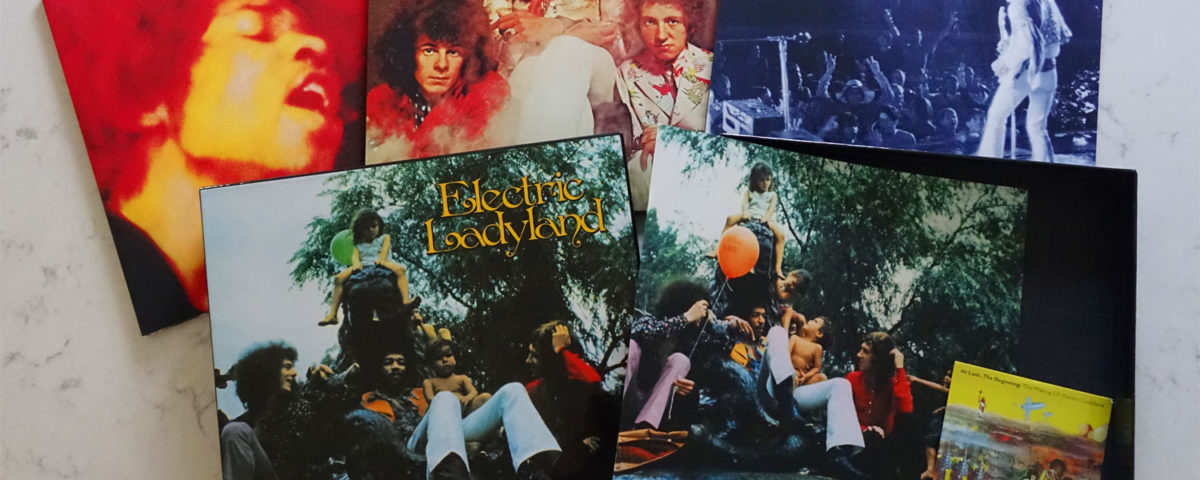

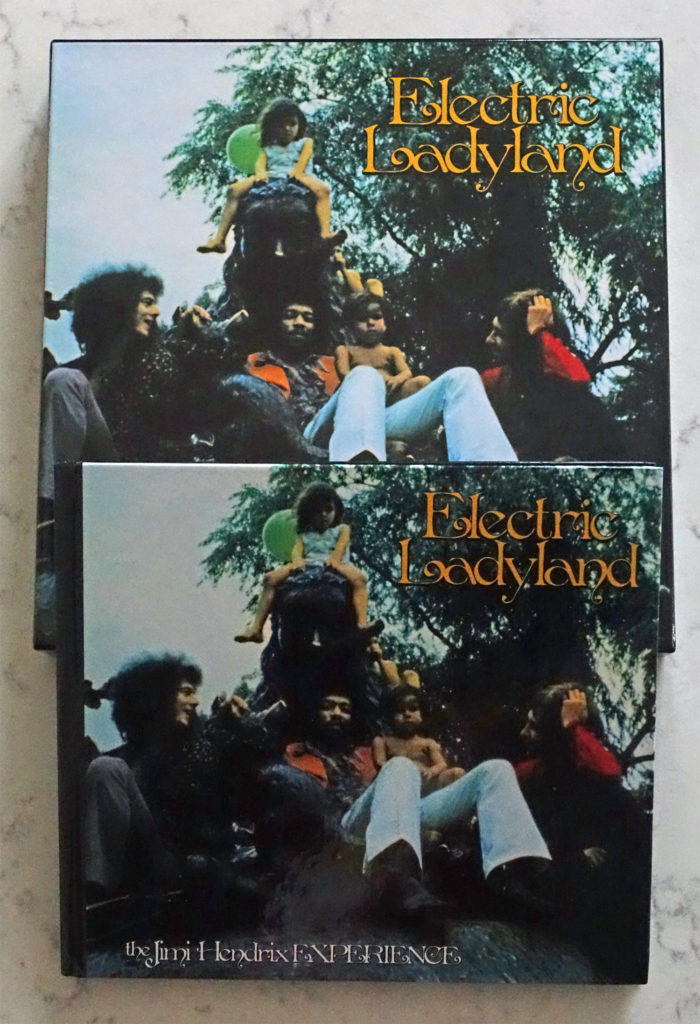

The vinyl variation of the 50th anniversary “Electric Ladyland” box set offers large, colorful covers for each of the three double-albums found within. The set’s separate booklet is also in a larger format than its CD counterpart, although the Blu Ray disc tumbles about untethered.

Ah, yes – the 50th anniversary edition of Electric Ladyland. Perhaps no release in 2018 was chatted about – and fretted over – to the extent of this package, issued toward the end of the year of a box-set-heavy rock music album schedule.

When rumors began to swirl that Experience Hendrix and Sony/Legacy were teaming up on a 50th anniversary edition box set of Electric Ladyland, your author was in a tough spot. The text of Modern Listener Guide: Jimi Hendrix was already in the capably creative hands of designer Gina Stewart. Cramming in one more lengthy review would certainly cause problems at this late date, perhaps pushing eBook and print book production well into 2019.

Once the rumors proved to be true, however, I realized this late-in-2018 box set created a perfect opportunity. I had always planned to continue writing new chapters of Modern Listener Guide: Jimi Hendrix after the book’s publication, one for each new release to emerge from the vaults. These chapters would be posted on this website, provided free for all to enjoy. This new iteration of Electric Ladyland would be perfect as the first of these supplemental chapters. Now I could refer to the 50th anniversary package, its contents, and its design in the eBook and print book editions of Modern Listener Guide: Jimi Hendrix while saving the critical and detailed analysis of the box set to serve as the first online chapter posted on this website.

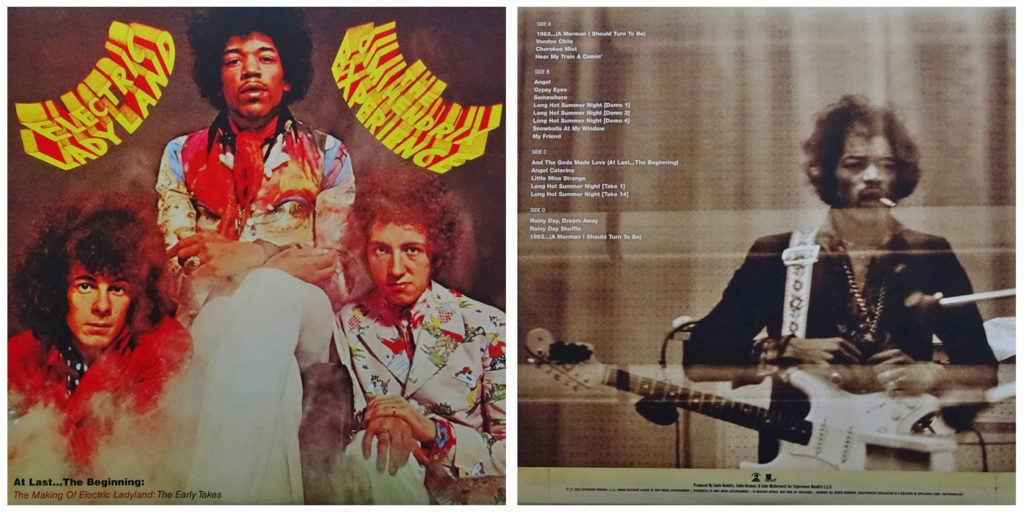

The cover of the demos and outtakes portion of the 50th anniversary “Electric Ladyland” box set – with the imposing title “At Last… The Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland: The Early Takes” – replicates an early Reprise Records cover design concept. This proposal was later rejected, though it was revived for use as album advertising.

For the casual modern listener, surely the most intriguing aspect found in this 50th anniversary exploration of Electric Ladyland is the presence of “never heard” demos and studio tracks grouped under the weighty title At Last… The Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland: The Early Takes.

Hmmm… Did the promotional material for this box set actually describe this material as “never heard?” Yes, it did. It’s true that the first dozen recordings in this group of 20 tracks date back to March 1968, captured at the Drake Hotel in New York as Jimi began to assemble his musical visions into coherency. Yet the first six of these recordings were commercially released decades ago, in 1995 as Jimi by Himself: The Home Recordings. This intriguing set of material is covered in detail within the pages of the print and eBook editions of Modern Listener Guide: Jimi Hendrix, so readers of this free bonus chapter are directed to either of those sources for the full story of these recordings.

So, that leaves just six demos in the category of truly unreleased. The lineup of this remaining half-dozen recordings begins with a skeletal version of a song familiar to experienced Hendrix listeners, “Somewhere.”

A full-band version of “Somewhere” with Stephen Stills on bass and Buddy Miles on drums was, like this demo, also recorded in March 1968, finally emerging on the People, Hell and Angels album in 2013. In that rendition, Hendrix lyrically imagined alien visitors totally mystified by the behavior of Earthlings.

The mournful lyrics of the “Somewhere” demo, however, bestow this slow version with what appears to be an account of the narrator’s mother being lynched in Mississippi – certainly a radical re-envisioning of the lyrics. This two-minute recording reflects how Jimi could be unsettled with regard to a song’s lyrical focus, even on versions committed to tape within days of each other.

The “Somewhere” demo also features the only appearance of another musician on the Drake Hotel recordings. The contribution comes in the form of forlorn harmonica contributed by none other than Jimi’s Greenwich Village pal Paul Caruso – humorously namechecked months earlier in the extraterrestrial interview that opens the Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Axis: Bold as Love album.

Jimi’s impressionistic lyrical side emerges on “Long Hot Summer Night,” expressed in a trio of two-minute versions identified as demos one, two, and four.

The first two takes are very similar, and clearly point the way to the song’s fully realized format as heard on Electric Ladyland. The similarities include both versions ending with a very brief bolero-like conclusion not utilized on the final studio rendition of the song.

“Demo 4,” however, curiously opens with lyrics that Jimi sings later in the studio recording of the song, the track seemingly beginning in the middle. This odd start inspired the sonic sleuths at the highly-regarded, all-Hendrix publication Jimpress to investigate some nagging aural suspicions. Their conclusion: “Demo 4” is actually a continuation of yet another “Long Hot Summer Night” Drake Hotel demo, one that appears on the outstanding West Coast Seattle Boy box set. This Jimpress revelation certainly makes sense factually, though the rationale for splitting one song across two different releases remains a bizarre unknown.

“Snowballs at My Window” brings a welcome dose of energy, but sadly – at the time of this recording – Jimi appears to have had little of the song worked out. With a laugh, he brings it to a halt in less than a minute, after fully singing just the first verse of at least five known to eventually exist. This song also has a curious backstory, as Jimi’s handwritten lyrics – first published back in 1993 in a book compiled by Bill Nitopi titled Cherokee Mist: The Lost Writings – clearly refer to it as “Our Lovely Home.” The reason for its 2018 retitling to “Snowballs at My Window” is a mystery.

The Drake Hotel collection comes to a conclusion with the influence of Bob Dylan in the air, as Hendrix documents his ideas for “My Friend.” The lyrics are full of abstract images, which would be more fully conveyed – complete with a rowdy barroom ambience – in the band version of the song, released in 1971 on the first posthumous Jimi Hendrix studio album, The Cry of Love. Interestingly, some of Jimi’s guitar approaches on this specific demo indicate the instrumental progressions and stylings of “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be)” were spreading into other tracks as well.

With that, At Last… The Beginning makes its transition from the 12 songs of solitude in Jimi’s New York hotel room to eight tracks captured in the creative confines of the recording studio. And that transition is jolting, the soundscape morphing from the sounds of Hendrix quietly documenting his thoughts to the sonic sculpture within an alternate swipe at “…And the Gods Made Love,” the spooky aural creation that opens Electric Ladyland.

The odd effects and disconcerting panning of this brief expression in sound soon yield to “Angel Caterina” which, despite its title, is essentially an early studio run through “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be).” It was recorded at Sound Center Studios on March 13, 1968 – the same night the full-band version of “Somewhere” mentioned earlier was also recorded. In fact, this very night saw quite a bit of musical cross-pollination, with rhythm section roles played at various points in the evening by Noel Redding, Mitch Mitchell, Stephen Stills, and Buddy Miles.

“Angel Catarina” receives a relaxed treatment at the hands of Hendrix with Redding on bass and Miles on drums. It’s clearly a test flight of the song’s elaborate structures, proving their durability. After all, they would soon serve as the very foundation of one of Hendrix’s greatest and most creative studio constructions.

Simpler by design – and certainly more energetic – is Noel Redding’s contribution to Electric Ladyland, “Little Miss Strange.” The early rendition of the song heard on At Last… The Beginning was cut at Sound Center Studios, also on that same fertile March 13 night in 1968. With more personnel shifting underway, Redding moves to guitar, Stills picks up his bass, and Miles remains behind the drum kit. Hendrix observes it all from the control room in his capacity as producer. While this instrumental recording shows Noel’s song is fully fleshed out, the urgent surge of the ultimate version heard on Electric Ladyland is missing in action, deservedly relegating this effort to demo status.

“Long Hot Summer Night” makes its fourth and fifth appearances on At Last… The Beginning with “Take 1” and “Take 14,” both recorded at the Record Plant on April 18, 1968, and both featuring Hendrix joined by Al Kooper on piano.

“Long Hot Summer Night (Take 1)” reveals many of the subtleties Jimi had in his rhythm guitar arsenal – subtleties all-too-often sacrificed on stage in favor of the high-volume broad strokes demanded by showmanship. Accompanied by a metronome quietly steadying the timing of the two musicians, Hendrix throws open his bag of rhythmic tricks, deploying everything from slides up and down the neck of his Stratocaster to seemingly off-time scrapes that reveal themselves to be perfect set-ups to chord changes. Kooper’s piano is more percussive than florid, but that just allows Jimi’s musical star to shine all the brighter.

Mitch Mitchell’s drums replace the metronome on “Long Hot Summer Night (Take 14),” as Hendrix and Kooper take full advantage of the additional percussive range offered by Mitchell’s drum kit. Its presence throughout the four minutes of this rough take allows Jimi to simplify his guitar parts, focusing more on the essential changes rather than generating a rhythmic surge. And while this is a rough take, things are definitely getting closer to the song’s full realization.

The fact that Noel Redding’s bass work does not appear on these recordings of “Long Hot Summer Night” was not necessarily a surprise by this point in the proceedings. As on other Electric Ladyland songs like “All Along the Watchtower” and “House Burning Down,” Hendrix simply devised his own bass lines, getting on with it himself when it came time to create finished backing tracks.

One of the most successful tracks on Electric Ladyland – and an exciting example of Jimi’s hunger to explore other genres of music – is “Rainy Day, Dream Away.” Mining the rich tradition of Hammond B-3 organ-driven soul-jazz, Hendrix supplements the customary guitar-organ-drums lineup of that style with the saxophone of Freddie Smith and Larry Faucette’s conga percussion. Drummer Buddy Miles is right at home swimming in these musical waters, and organist Mike Finnigan has often recalled Jimi suggesting to him that, for this track, they imagine themselves to be organist Jimmy Smith and guitarist Kenny Burrell – two of the leading proponents of this ultra-cool jazz genre.

While not quite boasting the slippery groove of the final take, this “Rainy Day, Dream Away” – recorded at the Record Plant six weeks after the “Long Hot Summer Night” cuts that precede it on At Last… The Beginning – has a brash strut that sets off Finnigan’s bold solo. Jimi coolly lays back until he chips in with a series of abrupt accent notes. He then briefly rolls off his Stratocaster’s treble control, but quickly reverts to the more prominent tonal presence he had claimed earlier. As Freddie Smith steps up for his own solo turn on sax, Hendrix’s backing becomes more aggressive, tremolo bar dives ominously circling around Finnigan’s pumping, left-hand organ bass notes. It all keeps surging forward, giving way to insistent repeated riffs as the cut builds to… A decidedly unceremonious and unfulfilling halt. In the studio, that’s just the way it goes sometimes.

On the jammy “Rainy Day Shuffle” the same personnel at the same Record Plant session morph the swagger of “Rainy Day, Dream Away” into a brisk trot, pulled-back cool giving way to a slightly more assertive heat. The structure is similar to the song’s namesake, but the feel is something else entirely. Buddy Miles is at ease with the musical acceleration, as is Mike Finnigan’s left hand, stirring up his bass runs on the Hammond. Jimi claims the first soloing spotlight, chasing tones ranging from amp-driven, breaking-up distortion to shimmering clarity. He then hands off to Finnigan near the two-minute mark, Hendrix slipping into a round of slinky, supportive comping. Soon Finnigan’s approaching the progression’s musical turnaround and really cooking. But jarringly, the music suddenly just stops, as though the recorder’s reel has simply run out of recording tape. Damn…

The At Last… The Beginning material wraps up with yet another early version of “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be),” this one appearing under its official title but without vocals, recorded April 22, 1968, at the Record Plant. Recorded six weeks after “Angel Caterina,” this rendition again finds Hendrix without Redding, teamed solely with drummer Mitch Mitchell in pursuit of at least part of a backing track for what was clearly becoming Jimi’s most ambitious song. And, significantly, this take outlines how and where some of the final track’s more abstract portions would eventually reside, the feel of the song taking on a resonating finality – including a dramatic build heralding arrival in the fabled realm of Atlantis.

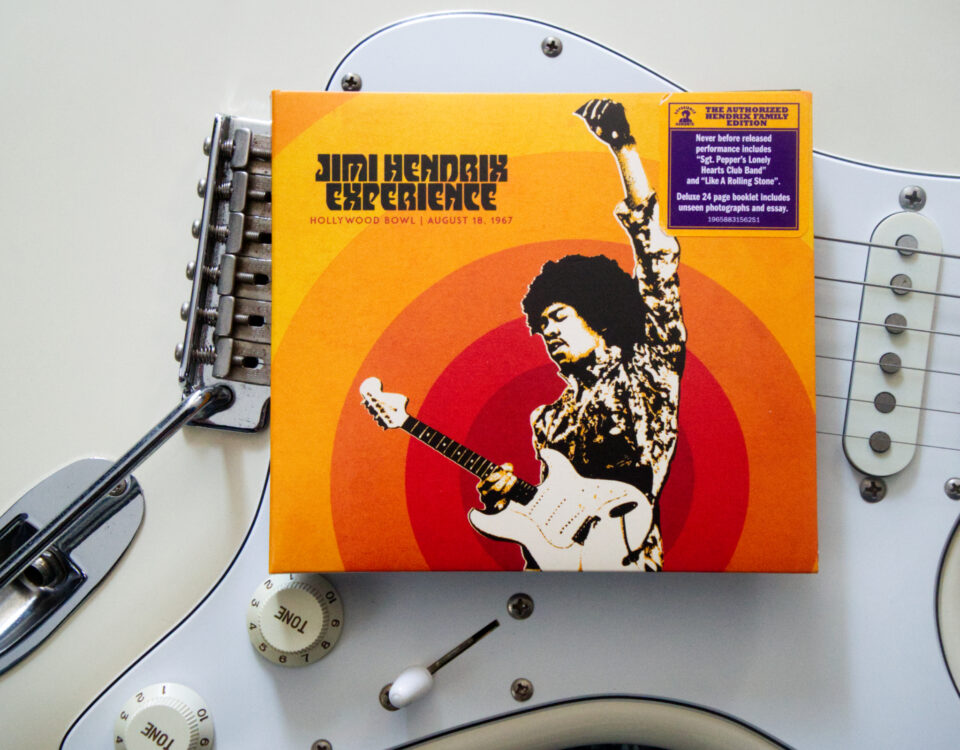

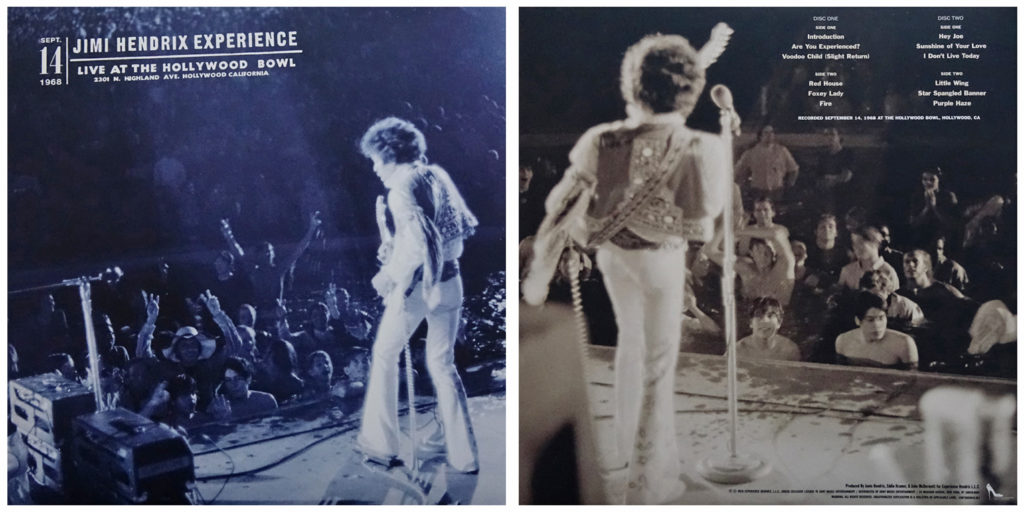

The “Live at the Hollywood Bowl” cover is curiously branded as an “official bootleg” Dagger Records release. Less curious on the recording itself is Noel Redding’s obvious concern about the potential for on-stage electrocution. The cavorting of splashing fans in the Hollywood Bowl’s large reflecting pool running the width of the stage created a quite real element of danger.

In the wake of the demos and outtakes collected on At Last… The Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland: The Early Takes we come upon a second group of never-released-commercially material within the confines of this 50th anniversary box set – and it has little to do with Electric Ladyland. Instead, Live at the Hollywood Bowl offers listeners a scruffy-sounding concert performance by the Jimi Hendrix Experience, captured in the period of commercial limbo between Electric Ladyland being completed and the double-album’s release.

The Experience played the Hollywood Bowl on September 14, 1968, their new album still a month away from hitting retail shelves. The trio had been far from idle since work finally wrapped up on Electric Ladyland two weeks earlier; indicative of the band’s frantic pace throughout 1968 the group had played nearly a dozen gigs in that short span, at locations ranging from Salt Lake City, Utah and Denver, Colorado to Vancouver, British Columbia and Oakland, California.

The day after the Oakland gig the Experience turned up in Los Angeles for an afternoon soundcheck at the imposing Hollywood Bowl, the concert shell’s then-unoccupied 16,000 seats stretching out before them. Closer at hand was the venue’s most unique feature: a large reflecting pool over 100 feet in width, shimmering 36 feet across the expanse stretching from the edge of the stage to the front rows of the seating area.

The Experience were already familiar with the Hollywood Bowl. They’d opened for The Mamas and The Papas in a concert there just weeks after making their incendiary American debut at the Monterey Pop festival in the summer of 1967. But now, a year later, the increasingly-popular trio was the headlining act. The pressure of the high-profile gig was focused squarely on Jimi Hendrix.

Live at the Hollywood Bowl opens with words of welcome for the Jimi Hendrix Experience from the venue’s local emcee. Following this short introduction – and a cheery “Hello!” followed by greetings from drummer Mitch Mitchell – listeners are treated to the usual accompaniment of booms, bangs, and rumbles from instruments being plugged in and mic stands being bumped into or moved. And of course, there’s the ever-present pre-song sounds of guitars being tuned in an era when the existence of small digital tuners couldn’t even be imagined. Mitch Mitchell’s bass drum likely had already been nailed in place to prevent any on-stage migrations of this largest piece of his kit.

Surveying the audience before him across the expanse of the 100,000-gallon reflecting pool, Hendrix is in a bubbly mood.

“Loosen up your tie, take off your wig, or whatever you’ve got on,” he giggles.

When the sounds come in earnest, this concert begins with a torrent of long tonal explorations. It’s ferocious if aimless chaos, the nonmusical violence eventually forcing Jimi into tune-on-the-fly mode before he makes serious entry into the first song proper, “Are You Experienced.” This is a fairly rare concert outing for the title track of the first Jimi Hendrix Experience album. The song benefits from Noel Redding’s agreeably present bass, solidly embracing the song’s root chord of A, but this version is not as forceful or focused as it could be. For all the potential “Are You Experienced” offers to blow minds as a set opener, at the Hollywood Bowl the Experience offer it up in nearly lackadaisical fashion.

More committed is “Voodoo Chile (Slight Return),” fresh as a new-song novelty and, before this night, played on stage just a handful of times. The song would eventually make its way to the end of Hendrix set lists as a closing number. But here, early in the show, the trio sticks close to the parameters of the album version soon to become familiar to listeners via Electric Ladyland. The no-frills approach is reinforced by Mitch Mitchell’s drumming, which at times sounds nearly monotonous – not a description often applied to the fiery drummer. But it’s also quite possible that many percussion subtleties are simply lost in this unrefined recording, a recurring symptom that plagues this show.

Surprisingly, Hendrix decides to slam on the brakes at this early point in the concert, calling for the slow blues of “Red House.” In the opening phrases Jimi coaxes soft billows of feedback from his amps on sustained notes, taking his time as he eases toward the first verse three minutes into the track. Entering the main solo two minutes later, Hendrix makes the most of the opportunity to instrumentally stretch out. Wrapping up his exploration, the guitarist eventually pulls back, Noel shifting to a walking bass line to introduce a conversational wah-wah passage.

The large crowd offers up polite applause in the wake of Jimi’s blues. But soon their enthusiasm quickly ramps up, matching the momentum of the Experience as the trio turns to two smash hits from their debut album, Are You Experienced. “Foxy Lady” and “Fire” successfully rile up the masses, though we modern listeners endure an awkward segue on the recording of these songs: whoever documented this show found it necessary to flip tape reels at this point, missing the end of the first song and the beginning of the second.

A giant reflecting pool lying between a wildly popular rock band and a rambunctious late-1960s audience? Is it any wonder we begin to hear evidence that the crowd is taking to the body of water as a means of getting closer to the stage? Noel jokes about swimming strokes, but the splashing enthusiasm of those who’ve entered the water will soon become a concern.

Jimi, though, is only concerned with continuing his perusal of his first album.

“We’ll slow the pace down a little bit,” he announces before ushering “Hey Joe” into existence with a lively, brisk intro. Redding and Mitchell join in as the group settles into a seething, restrained pace. Redding’s bass sounds edgy and distorted, though that’s more likely an overloaded tape recorder input rather than intentional amplifier distortion. This theory seems to be borne out mid-song as a subtle recording level reduction clears things up a bit.

Moving on in the set, Hendrix next announces the Experience’s intention to pay tribute to a fellow guitar-bass-drums power trio, Cream.

“Those cats are really out of sight,” Jimi sincerely complements.

Cream’s impending dissolution had recently been announced, and Hendrix decides he’ll honor their achievements by taking on one of the band’s best-known songs, “Sunshine of Your Love.”

“I’m not saying we can play it better than them,” Jimi admits with a laugh.

True enough. The rendition that follows is a shambling pass through the song’s elemental and riff-heavy structure, punctuated by a rare Noel Redding bass solo.

Hendrix next retreats to his own catalog with “I Don’t Live Today.” The song’s title threatens to become unintentionally appropriate: the lure of the pool has now grown irresistible to dozens of fans and watery chaos is breaking out at the feet of the Experience. All of this energetic splashing creates a hazardous situation thanks to the amplification and PA power lines strewn across the stage.

Diplomatic pleading eventually restores some order, and attention turns to Mitch Mitchell’s simple, relentless introduction. Hendrix steps forward to join Mitchell’s pounded beat with Stratocaster tremolo bar accents of wavering feedback. The song that follows is powerful if perfunctory. It’s enlivened by Jimi’s hectic outro solo which points the way to crashing closing chords. The fading musical roar is replaced by excited screams from the crowd.

Jimi seems to think the musical balm of one of the Experience’s most beautiful songs will calm the increasingly-frantic audience. So, he sets off into the Axis: Bold as Love ballad “Little Wing.” But several of his Stratocaster’s strings have drifted out of tune. Hendrix brings the song to a halt to correct the dissonance as Redding openly frets about possible electrocution for all in the pool vicinity.

Undaunted, Hendrix reinitiates “Little Wing.” This time he’s on a far more successful venture through the delicate twists and turns of the introduction. Redding and Mitchell soon follow their leader in empathetic support, resulting in a surprisingly effective performance – especially given the conditions. Though sound quality woes mar the recording, listeners can hear this was a thoughtful, fully realized take of the song.

Jimi then reveals his plan to play “The Star-Spangled Banner,” unnecessarily pleading, “Please don’t get mad…” It’s highly unlikely anyone in this audience is at risk of taking offense.

“You all just do anything you want,” he helpfully adds, “because this is the last song, alright?”

Not surprisingly, the anthem that follows is no match for the incandescent structure of the Woodstock performance that Hendrix would conjure up in just ten months. That later version, of course, was aided and abetted by the presence of the new Uni-Vibe effect, a unique sound processor that would quickly become a key sonic component of Hendrix’s guitar pedal arsenal.

Regardless, at the Hollywood Bowl “The Star-Spangled Banner” serves its purpose as a flamboyant introduction to the real set-closer, “Purple Haze.” The rhythm section crashes in effectively behind Hendrix’s tritone opening phrase, even if they are one beat behind upon entry, forced to quickly catch up. The energy coalesces into a compelling version of this early Experience hit. The trio sticks closely to the song’s structural script, and we can only assume the damp audience heads for the exits in a happy mood. That assumption must be made, as the source tape runs out seconds from song’s end.

Overall, the Jimi Hendrix Experience gave the Hollywood Bowl a decent performance on September 14, 1968. There were no major catastrophes from a gear-and-amplification perspective, which is always welcome in recordings of 1968 Experience shows. Still, the audience behavior in the pool – though amusing at times – was no doubt a significant distraction to the band, and Hendrix, Redding, and Mitchell don’t quite ascend to their highest musical peaks. Such heights would be easily and repeatedly attained by the group just over a month later during their fabulous San Francisco concerts largely documented on the Winterland box set, shows recorded as the release of Electric Ladyland grew imminent.

Oddly, Experience Hendrix has chosen to brand Live at the Hollywood Bowl as a separate Dagger Records release despite its inclusion in this 50th anniversary box set. True, tape flaws, interruptions, and the rough ending of Live at the Hollywood Bowl might be considered characteristic of other Dagger Records productions. After all, sonic perfection is never to be expected on releases issued by the “official bootleg” Hendrix label. But many purchasers of the 50th anniversary Electric Ladyland box set have raised what is a legitimate question: why has Experience Hendrix inserted an imperfect live recording of a fairly insignificant Jimi Hendrix Experience concert into a retrospective dedicated to Jimi’s greatest and most polished studio triumph?

Live at the Hollywood Bowl surely would have been welcome as a standalone Dagger Records release; in this box set context, it’s something of a party crasher when it comes to these Electric Ladyland birthday festivities.

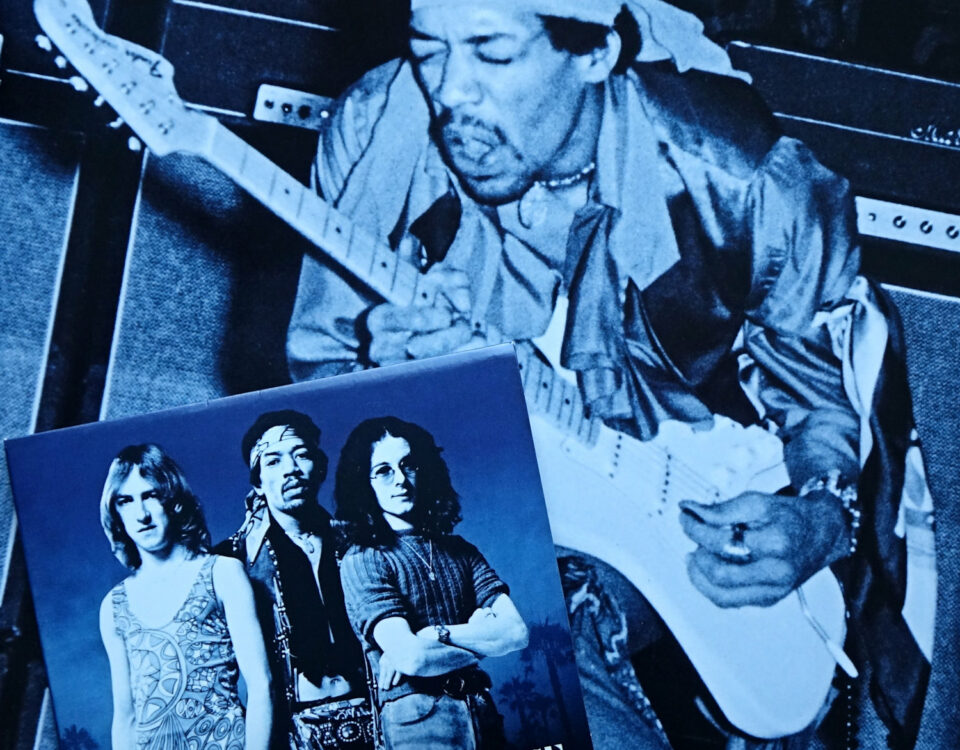

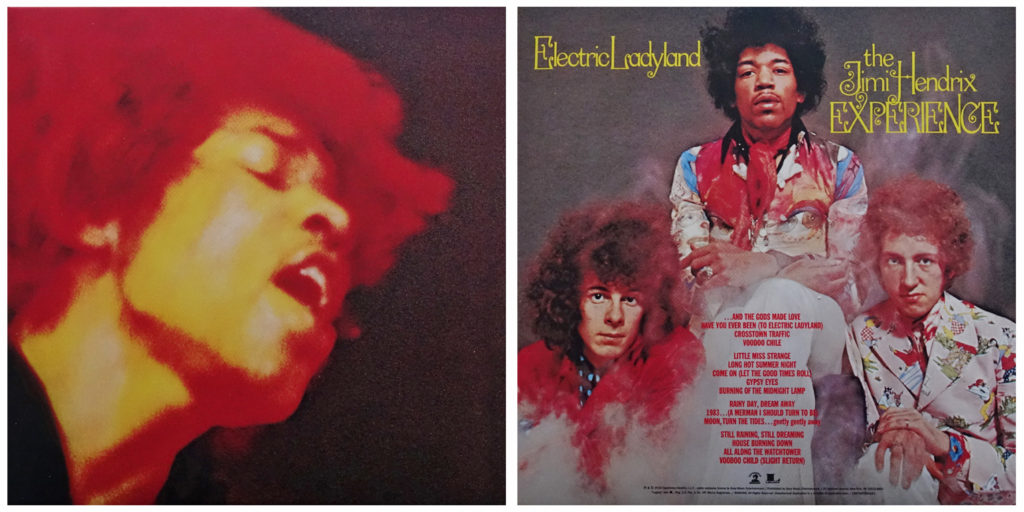

The familiar United States front and rear covers of “Electric Ladyland” – effective images, but artwork that completely ignored Jimi’s laboriously detailed instructions for how he envisioned the design of his third studio album.

Which brings us back to the reason for this box set’s very existence: Jimi Hendrix’s double-album masterpiece, Electric Ladyland.

In this review I will not go into great detail praising the bold creativity and ample displays of musical genius that run rampant throughout the 16 tracks that make up Electric Ladyland. For that in-depth analysis, I refer you to “Electric Landscape,” the eighth chapter of the print and eBook editions of Modern Listener Guide: Jimi Hendrix. Instead, let’s take a look at the Electric Ladyland formats to be found in this box set.

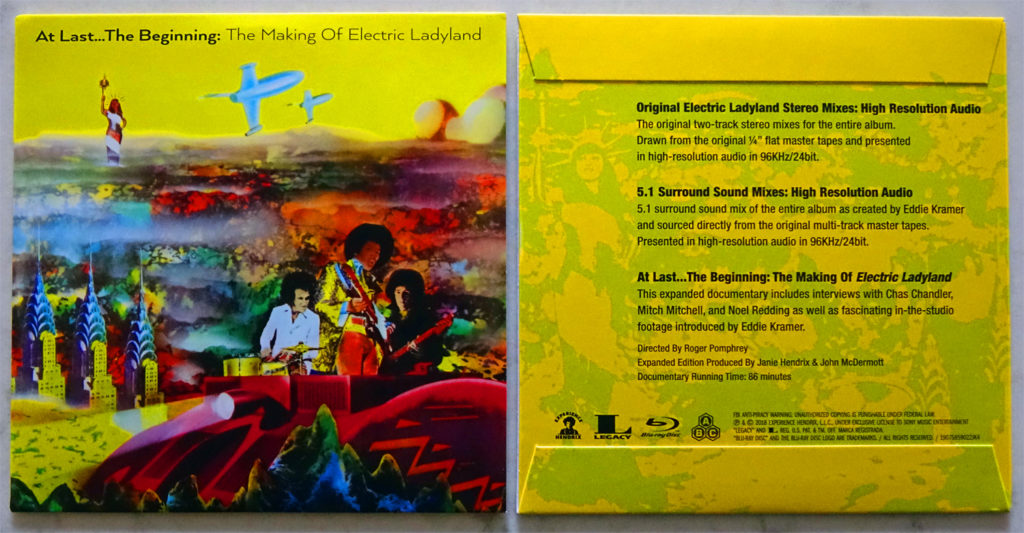

After perusing all the unreleased material, listeners will face a choice: Jimi’s ultimate creation is available for aural consumption in no less than three configurations in this 50th anniversary package. The original stereo mix appears on CD, or vinyl if that box set path has been chosen. And that same original mix also makes an appearance in the guise of a high-resolution 96KHz/24bit presentation on a Blu-ray disc included in both the CD and vinyl variations of the box set. Finally, this Blu-ray disc also offers Electric Ladyland in 5.1 surround.

It’s likely the majority of listeners will be turning to the CD of Electric Ladyland to hear the creative realization of Jimi Hendrix’s sonic visions. And some will do so with gritted teeth.

A number of consumers have grumbled about the audio mastering of this CD. Years ago, the music industry entered into what became known as “the loudness wars.” This conflict referred to an all-too-often-encountered audio ailment, one that was entirely self-inflicted by the industry itself. A mastering approach that sacrificed dynamic subtleties in favor of a perceived overall volume increase became all the rage, a trade-off that often made digital listening sessions tedious (for more background: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Loudness_war )

Though the aural conflict of the loudness wars peaked over a decade ago, fallout is still found on many releases to this day. A number of listeners have complained that the Electric Ladyland CD is mastered in such a way, with compression used to forcibly level out peaks at the expense of richer dynamics. Apparently, this mastering carries over to the high-resolution original stereo mix on the Blu-ray disc as well.

Of course, beauty is in the ear of the beholder, and obvious flaws to audiophiles may be sonically invisible to less-discerning listeners. And the odds are that anyone willing to pay the price of these box sets already has great interest in Jimi’s music. That means they likely already own at least one earlier and more sonically pleasing release of Electric Ladyland – if not a dozen or more such releases (your author is guilty as charged).

The cardboard cover that protects the Blu Ray disc bears yet another “Electric Ladyland” cover art variation from decades past, this one courtesy of Track Records. Oddly, these Track releases offered the double album “Electric Ladyland” content split into two single LP releases.

But what is truly new to everyone is Electric Ladyland translated into 5.1 surround format, resulting in a total re-envisioning of the source material’s mix. This surround mix is accessible for playback on the Blu-ray disc (not familiar with 5.1 surround? Check out: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/5.1_surround_sound ).

Messing about with the landmark, iconic Electric Ladyland mix, the sounds that launched a million mind-expanding sonic journeys? How dare they?

And yet, I am one modern listener who is glad they did.

Surround mixes run the gamut. Some amount to a collection of audio stunts, where excessive panning distracts from the music. In such cases the mixer seems more intent on showing off his own studio talents than sympathetically communicating the vision of the artist. On the other hand, some surround mixes are so timid the listener might find himself or herself sticking their ears up close to their rear speakers to investigate if any sound is actually coming out.

It’s a relief to discover that the 5.1 mix of Electric Ladyland strikes a perfect balance between these two extremes. Engineer Eddie Kramer revisits the material he helped record in the first place in an agreeably conservative manner, keeping in mind the artistic form of the original stereo mix. Yet he fully takes advantage of the opportunities provided by a surround mix for thoughtful reevaluation. The end result is a heedful mix that is also a revelation.

As a listener might expect, obvious targets in a 5.1 mix are long, sustained guitar notes, which can easily be given motion across the soundscape. But Kramer also focuses on more subtle marks. It’s now possible to clearly hear some of Jimi’s occasional vocal asides. And in “Voodoo Chile,” with Hendrix having recruited Jack Casady as guest musician, the bass now rumbles with a newly clear articulation. Casady’s work with Jefferson Airplane was always both distinctive and individualistic. Kramer now reveals those musical personality traits and allows them to make more of a contribution to one of Jimi’s heaviest blues songs. The bass was always present in the stereo mix, but now you immediately react: “Yep, that’s Casady…”

“Gypsy Eyes” is also particularly effective, ending with a writhing nest of guitars that suddenly fall away to reveal an all-too-brief snippet of Hendrix’s own propulsive bass line.

If Kramer ever flirts with going over the edge it’s on the closing track, “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” where the effects seem to fly just a bit too hard. Then again, that’s perhaps as much a matter of taste as it is a black-and-white sonic judgement.

Of course, of all the tracks on Electric Ladyland, the one offering the most potential for surround sound epiphany – or disaster – is the suite of “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be)” and “Moon, Turn the Tides… Gently, Gently Away,” Jimi Hendrix’s science fiction dream recast into sound. A 5.1 mix offers an opportunity for this familiar music to be pulled apart and redistributed.

Of course, such revelation could be a bad thing. Fortunately, listeners encounter a fascinating aural vista. The contents of the convoluted layers are exposed, spurring a new appreciation for the complexity and focus behind Jimi’s vision. And yet, in no way does this dissipate the vital force at the heart of the music. The curtains are judiciously pulled back just enough to lend a thrilling sense of how it was done. This new mix simply makes it clear what a remarkable achievement this piece of music really is.

The biggest flaw of this album’s entire ambitious 5.1 presentation actually has nothing to do with the music – it’s the amateurish looped slide show that visually accompanies the music. 19 photos of no apparent thematic connection endlessly repeat, superimposed over a green-tinted audience photo. Jimi Hendrix’s immense sounds deserve far better, and the only solution is to turn off your monitor or simply close your eyes and let your mind paint more interesting pictures.

And speaking of interesting pictures, the Blu-ray disc also contains the documentary At Last… The Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland. This documentary was and is still available as a standalone product. In Modern Listener Guide: Jimi Hendrix I described this documentary as follows: “An in-depth, revealing account of the creative efforts behind Jimi Hendrix’s studio masterpiece. Moments like organist Mike Finnigan’s humble tale of how he came to play on the album offer particular charm.” Those words are still fully applicable.

Remaining in the realm of visual aspects, the designs of these box sets commemorating the 50th anniversary of Electric Ladyland are decently attractive if not particularly imaginative.

Dimensional comparison of both formats of the 50th anniversary of “Electric Ladyland” box sets, with the book-like bound CD set on the bottom reclining upon the larger box that contains six vinyl LPs. Both covers reproduce an image from Linda McCartney’s 1968 Central Park photo session with the Jimi Hendrix Experience, a session which fortuitously included several children who were playing in the park that day.

The vinyl box is just that: an LP-sized box, with one of Linda McCartney’s portraits of the Experience with a group of children in Central Park on the front cover, as Jimi intended and specified five decades earlier. Copy detailing the set’s contents appears on the rear. Live at the Hollywood Bowl, At Last… The Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland: The Early Takes, and Electric Ladyland itself are all packaged as individual double-albums within the box, along with an LP-sized booklet. The Blu-ray disc is unceremoniously loose within the box, and there have been consumer reports of vinyl box sets that are missing the disc entirely – something I can verify from my own experience.

The CD edition mimics the cover material of the vinyl box, surrounding a bound book presentation measuring roughly 12 inches wide by 10 inches in height. Two pockets inside the front cover contain two of the set’s CDs, with pockets set into the rear cover bearing the third CD and the Blu-ray disc. The booklet content is identical to the vinyl box set with the exception of formatting changes required due to the different dimensions of the CD set.

The booklet contains essays from David Fricke and typically informative content from Experience Hendrix historian John McDermott, along with brief documentation from engineer Eddie Kramer about his approach to the 5.1 surround mix. But the real highlights are the wonderful photographs interspersed throughout, ranging from performance and in-studio photos of the Jimi Hendrix Experience to a large photograph captured at a 1968 UK promotional party celebrating the release of Electric Ladyland.

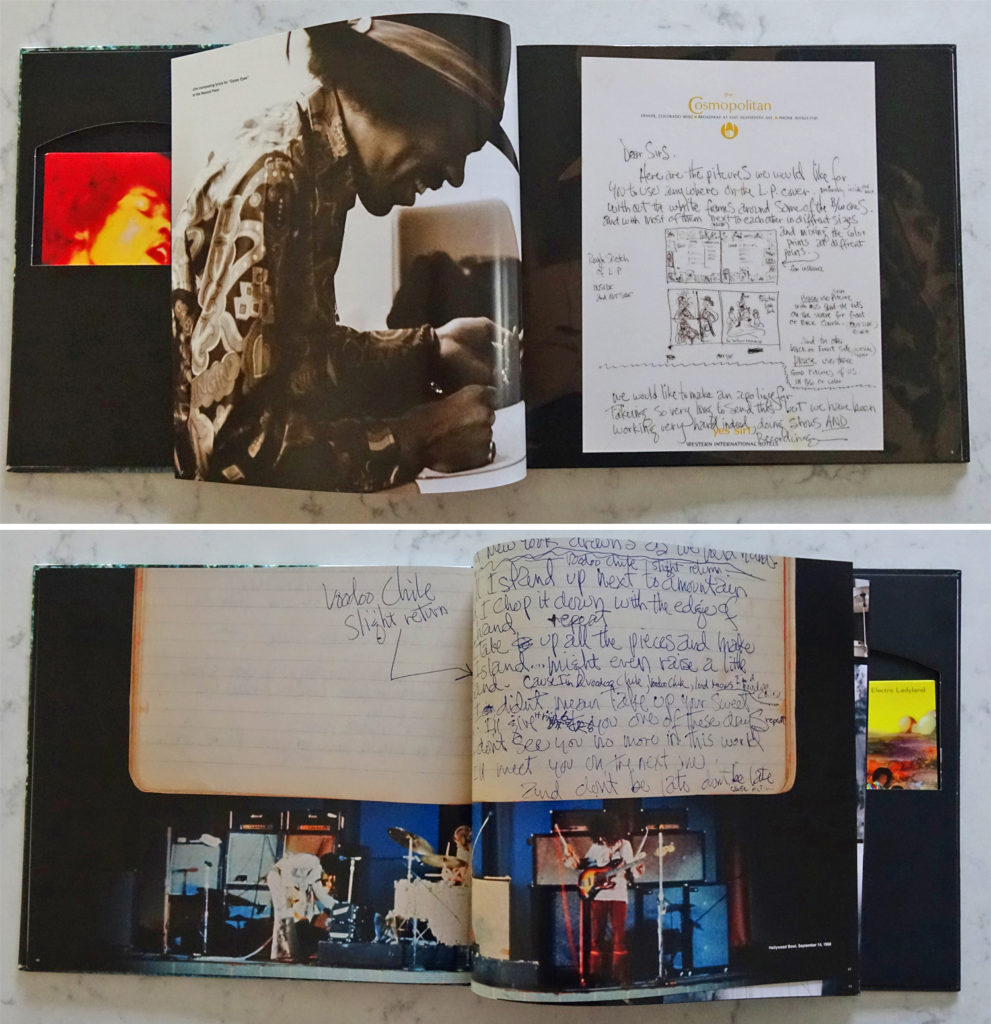

Examples of the attractive layout and design of the booklet accompanying the CD edition of the 50th anniversary of “Electric Ladyland” package. The CD booklet contents are identical to the vinyl box booklet with the exception of dimensional variations. The extensive reproduction of Jimi’s own writing is a highlight.

Also heavily featured in the book are page upon page of Jimi’s handwritten lyrics from the period of Electric Ladyland’s creation. All of these lyrics and notes written by Jimi have appeared previously in the beautiful and excellent Janie Hendrix and Experience Hendrix book project Jimi Hendrix: The Ultimate Lyric Book, a book that is highly recommended.

Oddly, Experience Hendrix seems to have had some trouble tracking what’s where and what it’s called. For example, the alternate rendition of “…And the Gods Made Love” appears in the box set booklet under the title “And The Gods Made Love (At Last… The Beginning).” On the back of the CD box set it’s titled just “At Last… The Beginning.” On the back of the vinyl LP and CD sleeves it reverts back to the box set liner notes titling, “And The Gods Made Love (At Last… The Beginning).” And though the track leads off the early takes studio material, it’s the very last song John McDermott writes about in the liner notes dedicated to that collection of material, joining “1983… (A Merman I Should Turn To Be)” as songs appearing out of order within those liner notes.

Takes one and four of “Long Hot Summer night” claim eleven substantial paragraphs in the book, of which only the final two document the song. The remainder detail how the Record Plant studios came into existence – fascinating for me, perhaps not so interesting to you.

In the end, the music of Electric Ladyland will long remain an intriguing, bold body of work. And the tracks gathered on At Last… The Beginning: The Making of Electric Ladyland: The Early Takes make it clear that the album didn’t spring from nowhere. They do a fair job of offering a glimpse of Jimi’s creative documentation of his ideas for the album.

Still, a listener might well wonder: is that all there is? We know for certain the answer to that question is a resounding no. Curios, alternate mixes, and different takes abound, all circulating in Jimi Hendrix collector circles. The wonders range from lovely, formative passes through “Have You Ever Been (to Electric Ladyland)” to twenty takes of “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” which document the song’s metamorphosis from skeletal idea to powerful sonic realization. This unofficial material is encountered by collectors in varying degrees of fidelity, but these box sets would have been ideal homes for these works-in-progress to be presented in pristine audio quality.

Alternatively, instead of doling out this rather random selection of outtakes, why didn’t Experience Hendrix delve into the time-honored tradition of bands ranging from the Beatles to King Crimson who have bestowed modern listeners with full alternate versions of iconic albums? Even if unforeseen circumstances wreaked havoc on a cut back in 1968 – like when Jimi’s broken string at the six-minute mark scuttles a to-that-point impressive early take of “Voodoo Chile” – there’s a modern studio solution: just gather some parts from other takes and assemble a composite track, as Alan Douglas did on Blues to create “Voodoo Chile Blues.” After all, Experience Hendrix themselves are certainly no strangers to these kinds of master tape manipulation.

Perhaps the most significant marketplace competition for the 50th anniversary of Electric Ladyland came in the form of another look back across the decades. The Beatles were contemporaries of Jimi Hendrix, their groundbreaking career as a live band winding its way to a conclusion as Hendrix’s star ascended. Just days before the 2018 Electric Ladyland box set emerged, a luxuriously expanded edition of The Beatles – less formally known as The White Album – was released to fully justifiable acclaim. Carefully curated with both imagination and attention to detail, its imposing presentation of six CDs covered in depth the original album and many demos, sessions, and alternate takes, all leading up to a Blu-ray disc featuring a 5.1 surround mix complementing supplemental hi-res versions of the album’s original stereo and mono mixes.

Breathtaking in its scale and ambition, the 50th birthday of The Beatles was the social event of the season. Electric Ladyland’s rival gathering, with its lone CD of demos and sessions and an unrelated CD documenting a merely passable concert performance, turned out to be a far more modest celebration – worth attending for its 5.1 surround highlight, but ultimately disappointing. It could have been so much more…