CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR: MAN VS. VOLCANO – JIMI ON MAUI

© Frank Moriarty, 2021

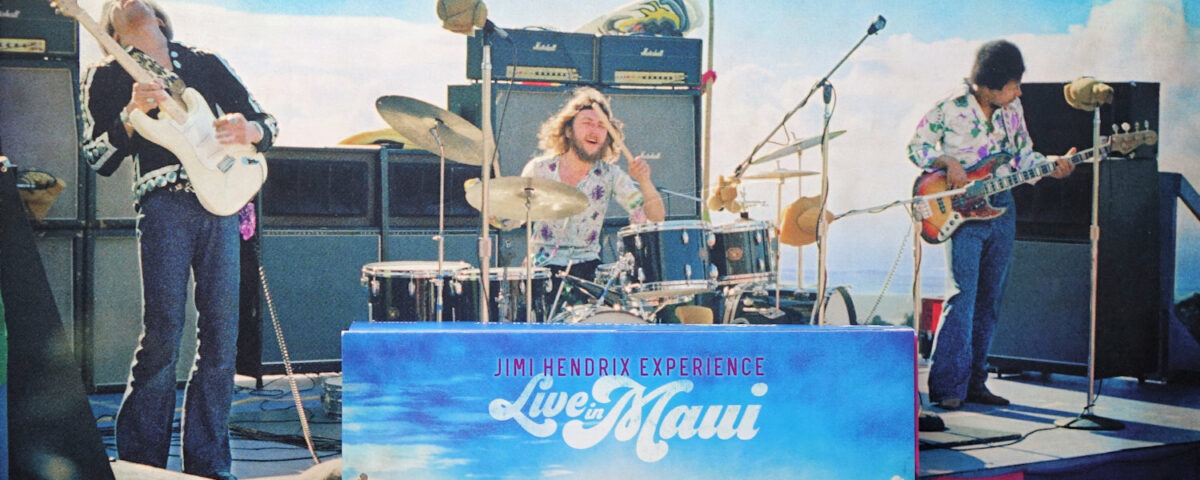

After the 2020-2021 chaos of recent months, a Hawaiian vacation sure sounds nice. And just in time, Experience Hendrix and Sony/Legacy have come to the rescue with Live in Maui – a collection spanning the two sets Jimi Hendrix, Billy Cox, and Mitch Mitchell played outdoors in Hawaii on July 30, 1970. Live in Maui? Well, as language sticklers by the dozens have noted, this release should correctly be titled “Live on Maui.” But here at Modern Listener Publishing we deal with whatever emerges from the vaults under any given name, so away we go!

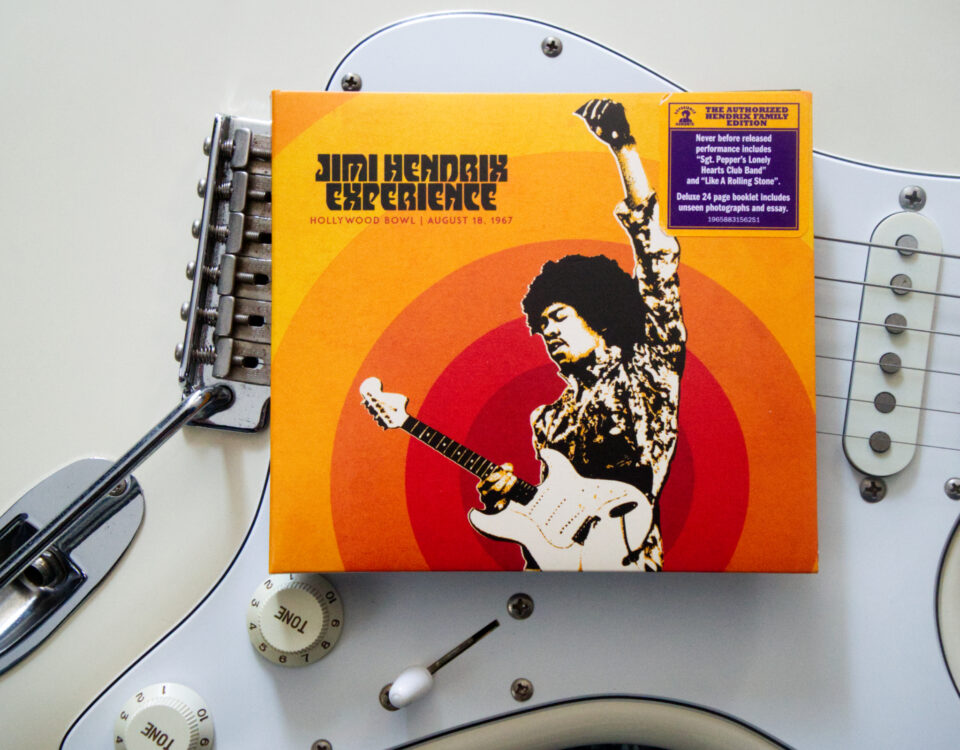

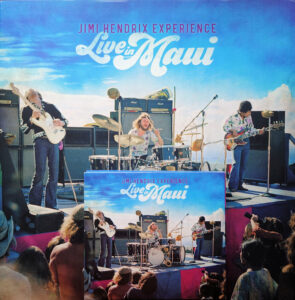

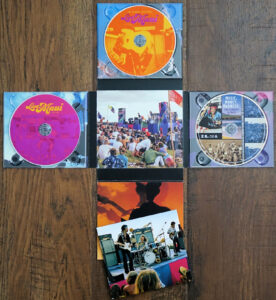

Live in Maui has emerged in the typical release specs that have characterized Jimi Hendrix releases of late: your choice of CDs (two, in this instance) or vinyl LPs (three), teamed up with video content on Blu-ray disc.

The CD and LP editions of Live in Maui both share the same colorful imagery, although a close look at the cover photograph reveals Jimi’s amplification has been reduced by one-half a speaker cabinet and one Marshall amp head via an airbrush effect.

To be honest, I’ve been suffering from Maui Malaise of late, which has delayed for a number of weeks the arrival of this online and free twenty-fourth chapter of Modern Listener Guide: Jimi Hendrix. We’ll address that later.

But before we proceed further, let me outline once again the ground rules for these free chapters: this online material acts as a supplement to the print and e-book editions of Modern Listener Guide: Jimi Hendrix. Therefore, it’s less formal and more conversational than what you’ll find should you purchase (which I surely hope you will) one of the available editions, which cover decades of Jimi Hendrix’s music within their pages. For a free taste of that published material, take a read through the chapter covering Jimi Hendrix’s creative uneasiness in the weeks leading up to his 1969 Woodstock performance, and an analysis of the historic performance he then unleashed at the festival:

https://www.modernlistenerpublishing.com/inside-the-book/

Just under a year after that Woodstock set, Jimi Hendrix had spent much of the summer of 1970 following a loose routine of studio sessions on weekdays with gigs supported by Cox and Mitchell on long weekends. As the summer waned, Hendrix closed out July and opened August with two appearances in Hawaii: a typical in-concert set at Honolulu International Center on August 1 preceded the day before by a gig that was anything but typical. This unusual concert consisted of two sets played in broad daylight among the foothills of the (fortunately) dormant Haleakala volcano.

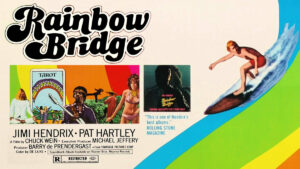

Wait – why on earth was Jimi Hendrix playing a concert on a volcano? The answer is that these performances were in service of the film concept that became known as Rainbow Bridge.

So, what was Rainbow Bridge? Well, Rolling Stone attempted to describe the general idea in the magazine’s August 5, 1971, issue, as the film was still being assembled:

(Hendrix) Manager Mike Jeffrey, director Chuck Wein and Warner Brothers thought (the concept) was a swell enough idea to sink $700,000 into a film about it.

The result, Rainbow Bridge, has enough going on: a Hendrix concert on the side of a volcano, Yoga, surfing, acid, clairvoyance, ecology (even), encounter groups, meditation, Zen, Tai Chi, flying saucers and Maui nookie. “I think the film says more than Easy Rider, really,” said Jeffrey. “It’s honest.”

The film certainly had potential to say a lot; the Rolling Stone article noted, “Word has it that Wein is taking the film, already edited down from 40 hours, back into the shed for further editing.” Those who have sat through any Rainbow Bridge iteration may be forgiven for shuddering at the thought of 40 hours of Wein’s visions.

But let’s dig a little deeper into the most existential of questions: what the hell was Rainbow Bridge, and how did it come to be?

Rainbow Bridge: much ado about… something. Exactly what still remains largely a mystery. Proceed with caution…

For as good and succinct an answer as I’ve ever come across, we turn to my friend Ken Voss, a highly-respected Jimi Hendrix historian (please explore his Facebook page dedicated to his long-running Jimi Hendrix Information Management Institute – or J.I.M.I. – which you can find here: https://www.facebook.com/groups/251427364936379 )

Ken was kind enough to offer me the use of his overview of Rainbow Bridge, as follows:

Allegedly facing a cash flow problem with construction of Electric Lady Studios, Jimi Hendrix manager Michael Jeffery reached out to Warner Brothers (the parent company of Jimi’s U.S. label Reprise), with the idea of making a movie. Through the proposal, Jeffery was able to get a $450,000 advance, promising a film soundtrack to the label.

As Maui was a favorite retreat for Jeffery, it was an ideal situation for him. During one of his trips there, he had met Mike Hynson, who was the star of The Endless Summer surf epic, and who was looking to develop another surf movie. With a proposed title Wave, the concept was to focus on the countercultural community on Maui. This island itself had become a mecca for the free-spirited counterculture living a Bohemian lifestyle in search of a universal nirvana.

Jeffery then contracts Chuck Wein, who was an entertainment promoter involved with alternative visual artist Andy Warhol, having produced three previous films for Andy Warhol’s Factory. And they make plans for what was to become Rainbow Bridge.

The resulting film was a disaster. The bulk of it focused on the occult, with only 17-minutes of Hendrix concert footage (and depending on the version released) a short two-minute segment with Hendrix talking.

Per the initial agreement with Warner Brothers, the only “real” Hendrix involvement was to provide an accompanying soundtrack. But as one review noted, “Rainbow Bridge was a snafu of impressive dimensions even for the hippie generation. It quickly became evident to Jeffery that the project desperately needed the presence of Hendrix on-screen if it was to have any chance of commercial lift-off. Plotless, script less and clueless, the film and its long-winded gestation is largely irrelevant.”

Thanks again to Ken Voss for this concise overview.

As Ken explained, with the Rainbow Bridge project gaining momentum, Jeffery realized he needed Hendrix’s active participation both for any chance of success and to cover the sizeable advance received from Warner Brothers, money that had largely already been spent. Since the current Experience iteration would already be on tour in Hawaii for an August 1, 1970, gig in Honolulu, Hendrix was coerced by his manager into playing two sets for the cameras while performing on the windswept hills around Maui’s Haleakala volcano. In tune with the hippie ideals at the core of Rainbow Bridge, the stage was adorned with colorful flowing fabric and, as Voss notes, “concertgoers were asked to sit in an area designated by their sign of the zodiac, each area designated by a banner of a different color.”

The tip of the “unofficial” iceberg. Jimi’s visit to Maui has long been of particular interest to Hendrix fans. Evidence of that can be seen in the many bootlegs and unofficial recordings that have emerged over the decades since the shows took place over fifty years ago.

Jimi’s visit to Maui and the recordings documenting his two sets played there have long been of particular interest to Hendrix fans. Evidence of that can be seen in the many bootlegs and unofficial recordings sourced from the Maui sets, material that has emerged over the five decades since the shows took place. While interest in the film was further raised upon Rainbow Bridge’s theatrical release in 1971 thanks to an excellent Hendrix-focused soundtrack album, the album’s grooves contained not a single note Jimi actually played in Hawaii.

Regardless of the Maui concerts being excluded from the Rainbow Bridge official soundtrack, Jimi’s volcanic performances have long been easily accessible to those willing to make the effort to track down the sounds.

And that creates a bit of dilemma. Collectors within the Jimi Hendrix realm have long had access to surprisingly good copies – both video and audio – of Maui source material. So now, after decades of being familiar with these two sets, many Hendrix fans find the appearance of Maui as a commercial release feeling like an incremental improvement rather than an earthshaking revelation.

The fact that “the thrill” has long been out of the bag – combined with a finely-honed sense of author procrastination – has resulted in this chapter not being composed until early in April, several months after Live in Maui became commercially available late in 2020.

Fortunately, time is definitely relative. These concerts were recorded more than five decades ago, so the delay of few weeks in reviewing their 2020 official emergence seems less egregious when viewed through that particular periscope.

The mainstays of Jimi’s road crew in Hawaii – Gerry Stickells, Eric Barrett, and Eugene McFadden – were no doubt thrilled at the prospect of lugging all of the band’s gear to a remote stage on the slopes of a volcano.

With excuses presented, we begin with the most complete aspect of Live in Maui, the audio recordings of Jimi’s two sets.

And right off the bat, we come across the seemingly inevitable: Experience Hendrix feeling the need to tamper with reality when it comes to presenting a “complete” Jimi Hendrix performance. It seems to happen just about every time, and Live in Maui is not the rare exception.

Hendrix, Cox, and Mitchell took the stage after a very brief introductory set – not heard on Live in Maui – by The Gemini Twins, two young women warbling harmonically over acoustic guitar backing. After inquiring, “Are you having difficulty hearing us?” they move on to celebrate the day in song, noting that “The sky is so beautiful, and the sun shines through in all its glory…”

The Twins – who have also been referred to as the Rainbow Band or Air – quickly yield the stage for opening remarks from the man who made this gathering possible, Chuck Wein, now basking in all his celestial glory.

“Welcome, cosmic brothers and sisters of Maui, to the Rainbow Bridge Vibratory Color Sound Experiment,” Wein begins, easing his way into setting the stage for the arrival of Hendrix and company.

Chuck promises Hendrix will arrive in “a few minutes.” On Live in Maui it’s all of five seconds before Jimi is heard initiating urgent staccato riffs on his Stratocaster, the guitarist almost immediately slowing down to ease into a mellow “Hey Baby (New Rising Sun.)”

That’s Live in Maui’s tale of the beginning.

In reality, Wein was indeed followed by a “few minutes” of anticipation for the music to come, time filled with the sounds of mics being bumped into, random drum hits as Mitch Mitchell settles in behind his kit, cables being plugged in, guitar and bass tuning, and the noise of the Hawaiian wind whipping around the mics.

“Give us about a minute to set up,” Jimi says after taking the stage and offering a quick greeting, “and we’ll forget about tomorrow and yesterday and get into our own little world for a while… Catch up to the wind.”

Another moment of stage-setting follows.

“I’d like to get into a thing called ‘Spanish Castle Magic,’” Hendrix advises laconically, “and check out everything and see what’s happening.” Hendrix counts off his heavy Axis: Bold as Love song, the trio then crafting a surging, scruffy rendition. Hendrix then follows this opening track with another up-tempo number, “Lover Man.”

In the Spring 2021 issue of the authoritative Hendrix publication Jimpress, Experience Hendrix historian John McDermott refers to these two songs – as well as a mid-set performance of “Message to Love” – as “three bonus songs.” The assignment of such status finds them extracted from the actual set running order and re-delegated as the final three songs on the first CD of Live in Maui. According to McDermott, “we elected to present these songs out of their original performance sequence for what hopefully is a better listening experience.”

Or you could have, you know, just served it up the way Jimi Hendrix himself did.

The reimagining of history has occurred so frequently on Jimi’s posthumous releases that most Hendrix fans are now simply numb to the tampering.

The bottom line: instead of launching with an explosive volley, Live in Maui begins with a ballad.

Following the mild sparks of Jimi’s solo introduction, “Hey Baby (New Rising Sun)” benefits from a focused performance as Hendrix, Cox, and Mitchell meander into the main structure. Renditions of Hendrix’s newer songs in 1970 concerts could be a touch hit-or-miss, but the trio here are all on the same page. Jimi deploys a relaxed chordal outro, which sets up a seamless, dramatic shift into high gear for “In From the Storm.”

Jimi remembers all of the words for this new song, avoiding a recurring problem at gigs throughout 1970. That creates its own issues, as Hendrix needs to rush the stream of lyrics a time or two to make them all fit.

Following this track, the remainder of the first Maui set consists of material which is much more familiar to the audience. The run begins with a fierce and fun “Foxy Lady” that briefly threatens to collapse as the song nears its end. Somehow the trio regains its musical footing and climbs toward a solid climax.

In an expansive mood, Jimi then offers a long and colorful introduction to “Hear My Train A-Comin’,” eventually revealing in a comic aside, “I don’t know what it’s about myself…” The song is at first offered up in slinky and restrained fashion, contrasting with the explosive version recorded in Berkeley two months earlier – ironically a version soon to become famous as the crown jewel of the Rainbow Bridge soundtrack album. Here Hendrix stomps on his fuzz pedal when he arrives at the solo, lighting things up with long notes portending the barrage of cascading runs down his Stratocaster fretboard that quickly follow. After a climax of notes issued from the highest fret positions, the sound clears as Jimi toys with the Strat’s tremolo, his wavering pitches a sonic reminder of those Hendrix explored in the Band of Gypsys version of “Machine Gun.”

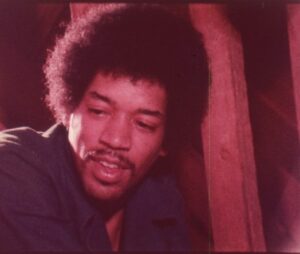

Jimi Hendrix on the Maui stage, in full magnificent flight. The relaxed surroundings of these shows led to many memorable performances crafted by Hendrix throughout the two sets.

A tight and intense “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” follows, Uni-Vibe swirl emerging late in the opening phrases to color the sound. Jimi plays with the effect pedal’s speed setting upon reaching the song’s lengthy solo section, before tiring of the sound and resorting to a simple combination of fuzz pedal filtered by wah-wah pedal. At the height of the instrumental passages Hendrix uncharacteristically urges the crowd to rise to their feet as the music steers toward a brief solo spot for Mitch Mitchell. Unusually, Jimi’s vow to meet his audience in the next world – “and don’t be late” – is missing in action.

Instead, following an unsettling segue, the trio builds toward the peak of this first set via a frantic “Fire,” one that includes two nods to Hendrix’s fellow power trio, Cream, in the midst of Jimi’s soloing.

“Purple Haze” closes this first show in enthusiastic, lumbering fashion, Jimi using his wah-wah pedal as a tonal filter for his fuzz-driven sound, forsaking the effect’s more common use as a vocal emulator. This rendition of “Purple Haze” is capped off with a quick quote of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” rendered in near-atonal fashion.

At this climactic moment Live in Maui presents “Spanish Castle Magic,” complete with Hendrix’s words of greeting to open the first set. Inevitably there’s a time-out-of-place sensation to the song’s new location as track nine. Jimi may have intended the song to be a throwaway performance to assess the trio’s sound on the unfamiliar stage, with no sound check taking place before the Maui sets. But this “Spanish Castle Magic” brusquely launches out of the gate, easily rising above the occasional squeal of unplanned feedback in raw and thrilling fashion. Its spontaneity conjures up a highlight of the entire day.

A Hendrix onstage favorite follows, with “Lover Man” receiving a perfunctory run through. Jimi relies heavily on wah-wah in the first part of the solo, that effect soon yielding to familiar legato passages.

The last of the transplanted first set performances is “Message to Love,” originally the fifth song in the running order. It was likely familiar to at least some of the audience, as it had been included on the then-new Band of Gypsys live album released just four months earlier. By the time Hendrix played the song on Maui, he had been presenting it in live settings for over a full year. Completely at ease, Jimi boldly leads Cox and Mitchell through the series of tightly-syncopated passages that characterize the verses. Hendrix then leaves the duo holding down the bottom as he launches into a tight, concise solo building on rhythmic elements. After the last verse Hendrix and Mitchell step out to indulge in a brief guitar-and-drums vamp before Cox falls back in as support for Jimi’s second solo. The trio then reunite to set up the song’s ascension toward its final chord, bringing to a close material from the first Maui set.

An image that truly captures the feel of the Maui sets, with Eric Barrett on the left dialing in the on-stage monitor mix as Jimi surveys the informality of the whole scene.

The entire second set appears in the proper order on Live in Maui. And where the first set had mainly been populated by reliable in-concert warhorses, the second set largely consisted of newer songs that Jimi Hendrix had been focused on throughout 1970. For this second half of the concert Hendrix also switches from his white Fender Stratocaster to his new, black Gibson Flying V. This guitar had been built and configured specifically for a left-handed guitarist, a benefit Jimi rarely had the chance to enjoy. As a result of this choice, the humbucker pickups in the Gibson color Jimi’s playing with a darker, thicker tonality up to the encore, when Jimi returned to his Fender guitar equipped with single-coil pickups.

To start the set Jimi chooses “Dolly Dagger,” a song he’d focused on deeply just four weeks earlier as he recorded in his new Electric Lady Studios on West 8th Street in New York’s Greenwich Village. In the studio Hendrix had laid down a solid backing track, then returned to the song several times in the intervening days. In this concert setting, “Dolly Dagger” sets off on sluggish footing, and Jimi loses track of some of his lyrics. But as they move on Jimi’s trio solidifies their approach. Confidently riding the song’s changes, the band locks in on the structural complexities of Hendrix’s progressions. The momentum sets up an edgy wah-wah solo that caps off the performance, Hendrix reaching for the highest notes to be found on his new, angular guitar’s neck.

Carrying on from those heights, Hendrix begins to rein in Cox and Mitchell, easily vamping his way through a reduction in velocity and intensity. What then unfolds is “Villanova Junction.” This lovely instrumental was first heard in concert nearly a full year earlier, a moment of calm amid the chaotic Woodstock set performed by Jimi’s Gypsy Sun and Rainbows aggregation. Drenched in the watery, wavering ambience of the Uni-Vibe, Hendrix’s playing reflects the new directions he had been exploring throughout 1970. Eventually Jimi brings the music down to a hush, using light percussive taps and string scrapes to set up a brief diversion into pseudo-flamenco territory – and inexplicably incorporates a line of “The Little Drummer Boy” into the proceedings. Christmas in July!

Jimi and Mitch diverge into a short percussion duel leading to another of Hendrix’s newest compositions, “Ezy Ryder.” The track carries the set toward a renewed head of steam, pushed forward by Mitch’s surges and Jimi’s driving open strings. The approach is entirely appropriate for this hardest-rocking song of Jimi’s recent compositions.

The crowd is receptive to this vibrant transfer of energy amid the volcanic Maui influence, but Jimi decides to lower the temperature again with the slow blues of “Red House.” Every live version of this song is unique, the Maui rendition’s six-minute duration being quite compact compared to lengthier excursions like the twelve-minute adventure recorded in San Diego on May 24, 1969. Here Hendrix is relaxed as he follows the musical path through one of his oldest songs, staying on track and shunning any excess.

From the blues Jimi returns to his fertile 1970 songbook and selects “Freedom,” which eight months later would serve as the lead-off cut of the first posthumous Jimi Hendrix album, The Cry of Love. Billy’s inventive-but-funky bass line anchors the track. While setting up the chord changes to support Hendrix, Cox also fulfills an equally important responsibility by caretaking the track’s overall musical momentum.

At Woodstock Hendrix had played a second new instrumental, one that came to be known under two titles, “Jam Back at the House” and “Beginning.” The song had received attention in the studio after Woodstock, but it had not been played on stage since that festival appearance. But the focus dedicated to the song in the studio pays dividends when Jimi decides to add it to his Maui set list. The trio confidently attack the tricky, syncopated construction to make the presentation a successful one.

As “Jam Back at the House” winds down, Jimi briefly conjures up the eerie presence of “Cherokee Mist,” yet another instrumental and one that Jimi had seemingly been fascinated with since early in 1968. But the visitation is brief, as Hendrix quickly guides the band into a partial-yet-energetic rendition of “Straight Ahead,” the song that would later kick off the second side of The Cry of Love.

The three musicians delve into this new song in hypnotic, driving fashion, oddly beginning with a later verse of the song. A chorus naturally follows, before the band finally makes their way instrumentally back to the verse structure. The attack then simplifies into an alternating two-chord section. This acts as a foundation, freeing Jimi to launch a climb up the neck of his Gibson. Suddenly, a plummeting, freestyle legato descent changes everything, and the trio finally comes to a halt. Jimi’s Uni-Vibe offers a brief, sighing punctuation to the now-concluded excursion.

Pondering his next path, Hendrix initiates a pensive series of instrumental phrases, his tone clean and uncolored save for a now-subtle setting on the Uni-Vibe. Delicate octave runs unfold into the day’s second rendition of “Hey Baby (New Rising Sun),” though far less complete than the version from the first set. Instead, it acts as an instrumental placeholder, with Jimi apparently reconsidering the idea of singing material he’d already covered.

Abruptly, Hendrix transitions briefly into “Midnight Lightning,” a dark, brooding blues the audience is no doubt unfamiliar with. Seconds later he’s moved on to “Race with the Devil,” a nod to the band Gun and its founders, brothers Adrian and Paul Gurvitz. Jimi frequently quoted this song during his 1970 concerts, but here he uses an extended solo over the Gurvitz progression to conclude this exciting and totally unpredictable second set.

In the wake of such a meandering musical journey, Hendrix decides to reward the wind-blown crowd with something familiar as an encore: “Stone Free,” first released three years before. This version is loose and energetic, and emboldens Hendrix almost enough to segue into another early hit, “Hey Joe.” But Jimi – after teasing out a few words of his very first single – reconsiders, instead charting an alternate course toward a frantic instrumental climax, bringing his Maui sets to a satisfying close.

A favorite promotional photo from the Modern Listener Archives shows Jimi on the Maui stage but identifies the source as Berkeley. The caption goes further off the rails by claiming Hendrix is playing “House of the Rising Sun,” a song never known to have made its way into any of Jimi’s set lists.

In context, both sets played at Maui that windy day were relaxed, nearly informal performances that allowed Hendrix to stretch out musically. The circumstances and the relatively small, happily welcoming crowd provided Jimi with an opportunity: to follow daring sonic paths he may have hesitated to pursue when performing in the darkness before a restless arena audience.

For the music fan unfamiliar with most – or even any – of Jimi Hendrix’s concert on Maui more than five decades ago, Live in Maui will be a revelation. For the deeply-committed Hendrix fans who have long been acquainted with the music made that day, the revelation will be incremental through an improvement in the overall sound quality of these sets. Nevertheless, that improvement alone makes this box set absolutely essential.

With that said, we turn now to the visual aspects of the Live in Maui packages.

As explained earlier, the presence of Jimi Hendrix at these concerts was in support of the filming of a movie envisioned by Jimi’s manager, Michael Jeffery, and director Chuck Wein as the end-all, be-all cinematic crystallization of hippie ideals and cosmic meandering. And that it may well have been. Over the decades Rainbow Bridge has appeared in various formats, edits, and lengths. Viewers may find the opening segments of the film to have a certain spacey charm of the period, but most will agree that charm soon wears off, morphing into an excruciating descent into post-psychedelic morass. The end reward is meager: brief moments when the persona of Jimi Hendrix inhabits the film.

Of course, the making of any movie bears a tale, and the telling of the Rainbow Bridge story takes up the lion’s share of Live in Maui’s Blu-ray disc content with the documentary Music, Money, Madness… Jimi Hendrix in Maui.

The CD (above) and LP (below) packaging of Live in Maui in their fully expanded states. In the CD set the Blu-ray disc bearing a documentary and footage of Hendrix, Cox, and Mitchell in concert has its own mounting incorporated into the packaging; the Blu-ray in the LP set is contained within a cardboard sleeve and is found untethered within the collection.

This program takes an in-depth approach, presenting interviews that range from key Rainbow Bridge production people like art director/cast member Melinda Merryweather to local Maui residents who were all too happy to climb on board the Warner Brothers-funded venture. And for that matter, some who were not too happy also appear: Ken Melrose recalls how his father, the headmaster of Seabury Hall, had rented out the religious school for girls to act as Rainbow Bridge headquarters and was soon horrified by the antics of Chuck Wein and his hippie cast and crew.

Particularly revealing in Music, Money, Madness… Jimi Hendrix in Maui is the path Wein had followed to end up helming film production in Hawaii using other people’s money.

Wein had envisioned his own stairway to the stars through factory work in New York City. Andy Warhol’s Factory, that is: the ever-evolving, artistically bleeding-edge entity of the 1960s that orbited around the influential artist. In early 1965 Wein parleyed his relationship with a fledgling Warhol star – the beautiful Edie Sedgewick, whose life story would sadly play out as a tragedy – as a crowbar to pry open the Factory doors so he could step through. And once inside, Wein made the most of his opportunity – while putting off many of Andy’s arty associates.

For those with an appreciation of Warhol – or at least a curiosity about this enigmatic figure – this segment is one of the most interesting aspects of Music, Money, Madness… Jimi Hendrix in Maui, especially the perspective given through the fully unfiltered thoughts of Warhol inner circle resident Victor Bockris.

Unfortunately, Jimi Hendrix appears in the documentary as little more than another cast member, despite his unwitting responsibility for the success or failure of the entire venture. In fact, Hendrix is most frequently seen via the same practice Experience Hendrix has relied on in documentaries of the past: brief glimpses of Jimi on stage extracted from unrelated concerts.

The inclusion of this fairly interesting 90-minute documentary as part of Live in Maui is all well and good, but no-one will argue that the true beating heart of the Blu-ray disc is the thrilling film footage of Jimi Hendrix, Billy Cox, and Mitch Mitchell in concert on the volcanic slopes. Thrilling – yet frustrating.

Experience Hendrix has indicated that whatever concert footage exists in this wide world can now be found on this Blu-ray. That’s an exaggeration. Despite Experience Hendrix’s John McDermott stating in Jimpress that Live in Maui has “all of the existing 16mm and 35mm footage that we were able to find,” collectors know there is at least some content missing. But let’s give the producers accolades by settling for this material being “just about all.”

So, what does that amount to? The Maui audio recordings total roughly 100 minutes; the film footage program tops out at just over 70 minutes. As you might imagine based on that timing, there are obviously significant portions of the concert missing. The three songs displaced from their location in the first set for the Live in Maui audio content – “Spanish Castle Magic,” “Love Man,” and “Message to Love” – are not represented in film footage. And the core second set stretch from “Jam Back at the House” to Jimi’s brief flirtation with “Midnight Lightning” and the “Race with the Devil” finale are also missing in action.

It’s also noteworthy that not all of the 70-minute running time is actual concert footage: occasional lengthy gaps in the presentation are filled with random footage, still photographs, or the notification “All Cameras Stopped.” The latter is particularly curious. Everyone simply happened to stop filming at the same time on multiple occasions? Or is it a case of footage having been sloppily destroyed or simply lost during the original Rainbow Bridge editing process back in 1971? As I said: frustrating.

But the footage that does exist? Priceless!

Particularly exciting material is seen throughout the first set thanks to a camera located toward the back of the crowd. As anyone who has watched concert films from this era knows, camera operators back then loved their closeups. So much footage of Jimi Hendrix in concert consists of extreme closeups of his face or his fingers, the claustrophobic cinematic experience rarely yielding full-length shots let alone entire stage views. That encumbrance is gloriously rectified here via long shots of Jimi and his Marshall amplification or Jimi and Mitch in musical communication. There are several moments when Jimi, Mitch, and Billy are all in frame, and the camera even pulls back further to capture the full stage. For these wonderful moments it’s possible to get a sense of what it was like watching Jimi on stage: how he moves, manipulates his effects chain, passes musical cues to Mitch and Billy with a nod or a lean to the side.

The second set material is largely filmed by a single camera at a medium distance stage-right, but this footage also places space around Jimi, further revealing his movements and pure charisma.

The oddest moments in the entirety of Live in Maui footage involve those depicting a two-man film crew barging their way onto the stage. They clumsily traipse about, eventually taking up position to Mitch’s right, with their lens just inches from Jimi’s shoulder. Hendrix simply carries on, though the result of this obnoxious intrusion into Jimi’s personal stage space is the kind of shaky, too-close imagery referred to earlier. In one long-camera shot later the two can be seen exiting the platform, bumbling down the steps stage-left. In the process they pass Jimi’s road manager Gerry Stickells, who appears to give them a disgusted “get outta here” wave. Undaunted, the duo returns for the encore, “Stone Free,” once again crowding Jimi as he attempts to focus on his Stratocaster.

It’s clear there was greater multi-camera coverage during the first set. It’s at least conceivable that Hendrix agreed to incorporate his best-known hits – “Foxy Lady,” “Fire,” “Purple Haze” – into the opening performance. With those songs captured, the crew left just the lone stage-right camera filming for the vast majority of the second set. Happily, this set features a long, unbroken segment comprising “Dolly Dagger,” “Villanova Junction, and “Ezy Ryder” that is simply outstanding.

Mitch Mitchell’s Maui mood is evident: a break in the touring routine, his wife in attendance, fresh air and spectacular scenery. Mitch was likely far less amused when the need to recreate his Maui performances became apparent.

There’s an interesting aside to the role this footage played in Rainbow Bridge. When the film was initially reviewed a technical issue became apparent: the winds whipping across the volcano slopes on Maui were quite noticeable on the drum track microphones. With roughly 17 minutes of the concert selected for inclusion in the movie, it was decided the best way to deal with the wind noise was to draft Mitch Mitchell to return to Electric Lady Studios in 1971. Mitch’s challenge? Attempt to recreate his drum parts from the year before, this time in the controlled studio environment. Under the supervision of long-time Hendrix engineer Eddie Kramer, Mitchell worked on the tracks slated for the film, largely material extracted from the first set. This included “Foxy Lady,” “Hear My Train A-Comin’,” “Voodoo Child (Slight Return),” a brief drum solo transitioning into “Fire”, and “Purple Haze.”

Nearly five decades later, Kramer – reprising his customary modern-day Experience Hendrix role as chief engineer and project co-producer – was able to virtually eliminate the sonic wind issues from the remaining tracks which did not receive drum overdubs, using studio technology unimaginable in 1971.

The star of the show arrives on the movie’s set, primed for a rational discussion with director Chuck Wein. On second thought, strike “rational” – this isn’t known as “the stoned rap” for nothing. Was Jimi merely toying with Wein? You be the judge!

Aside from the concert footage included in Live in Maui, it’s a shame that Jimi’s brief off-stage appearances in Rainbow Bridge are not included as bonus video material. This, of course, would include the infamous so-called “stoned rap” in which Jimi – apparently under the influence of some type of inebriation – delivers a stream of verbal mumbo jumbo which only an enthralled Chuck Wein seems able to understand. Long-time Hendrix fans will recall that a transcript of this bizarre conversation was illegibly printed in a light orange font superimposed on a hectic background image as part of the inner gatefold art of the Rainbow Bridge: Original Motion Picture Soundtrack album.

For that matter – though it’s easy to imagine contractual issues prevented this – it would have been appropriate to include the full cut of Rainbow Bridge as a Blu-ray component of Live in Maui. No, the film isn’t exactly cohesive, scintillating viewing, but including the ultimate realization of all of these efforts would certainly have provided historical context for the entire package.

Still, taken as a whole, Live in Maui presents literally hours of entertaining listening and viewing. Yes, it’s possible to quibble with some presentation decisions and to feel regret about all the footage that apparently went missing long ago, but it’s easier and more appropriate to simply welcome this release with wide open eyes and ears.

Image Credits: Experience Hendrix/Live in Maui packaging; Modern Listener Archives; Transvue Pictures; New Line Cinema.